Integration or

Transformation?

Integration or

Transformation?

A cross-national study of information and communication technology in school education

|

|

|

Chapter 5 Discussion

5.1 Introduction

Data for the study was collected from 1999 to 2002. This chapter synthesises the findings of the study together with the research described in the literature review to answer the four research questions and consider three propositions about the future development of ICT in school education. The chapter describes how the findings were used to develop and propose a model of development for ICT in school education, and demonstrates its application to Australia. The chapter concludes with recommendations for action and for future research.

The research questions posed at the end of Chapter 1 have provided an organisational framework for this study. This section shows how the findings have confirmed, disconfirmed and extended previous research in the field of ICT in school education.

5.2 The findings in relation to the literature

5.2.1 Research questions 1a and 1b

Research Question 1a: What has been the general nature of policies in the USA, England and Estonia for ICT in school education?

Research Question 1b: What were the development and implementation processes of these policies?

5.2.1.1 Initial vision for ICT policy

The process of policy development according to the expert panel depended greatly upon an initial vision; in many cases attributed in the political sphere to vice-president Al Gore (BM21; TE72-74; DM36; Gore, 1994a) and referred to in the literature as the ‘Gore-effect’ (Klumpp & Schwemmle, 2000). In many cases there was political mileage to be made from education and ICT in particular (DM36), and having invested so much money in the area, many politicians are now politically unable to withdraw support (KB155) which can be scheduled to peak as elections approach (BM24). Clarity of vision did not always persist in the writing process (KB105) and this political impetus for ICT in school education did not offer a clarity of vision or purpose that has persevered. This is partly due to the high rate of change of ICT technology (Bitter & Pearson, 2002, p. 1; Zakon, 1999) which makes policy review essential on a regular basis to address these previously unforeseen events (Dunn, 1994, p. 351). The expert panel and case studies confirmed the existence of a ‘technology push’ which was restricted by conservatism typified by an emphasis on student knowledge of facts (MR53, EM46) or an insistence that high-stakes examinations were conducted using hand writing (Plomp, Anderson & Kontogiannopoulou-Polydorides, 1996, pp.11 & 17; OECD, 2001, p.13; Eurydice, 2001, p. 19) despite most student day-to-day work being completed using a computer (KM60). It is unclear how policy-makers can best respond to this technology push; whether by constructing policies which are anticipative and adaptable, or by allowing for regular review and modification.

5.2.1.2 Pedagogical rationale

For ICT to get onto the agenda of national policy makers in education, it had to offer some advantage. The previous analysis of the three rationales (Hawkridge, 1989; Fabos and Young, 1999, p.218; OECD, 2001; Capper, 2003, p.63) is useful for examining the possible advantages which could be considered. The pedagogical rationale was difficult to justify with the research evidence in the literature indicating ICT has about the same impact as any other innovation (Parr, 2000). However, the expert panel and case study evidence (see Pärnu Nüdupargi Gùmnaasium) partially confirmed the literature about ICT increasing learner autonomy (IAEEA, 1999) with this aspect of the use of ICT included in English policy and observed in Australian schools. Measures of ICT effectiveness were often confounded with ICT integration (Woodhurst, 2002), and concentrated on student learning outcomes against criteria established prior to widespread use of ICT which were not considered appropriate when ICT was a significant element of classroom practice (Fouts, 2000, p.5). The relevance of using existing curriculum benchmarks will be examined in the following section under Research Question 3. Not only is this issue crucial to the substantiation of policy purporting to assert the pedagogical rationale, it is also vital in the justification and demonstration of ‘relative advantage’ for teacher professional development.

5.2.1.3 Social rationale

The social rationale embraced in Estonia is echoed by rhetoric about open government in England (Allan, 2000). ICT offers governments a very low cost way to deliver information and services to much of the population, providing telecommunications generally pre-existing, are available (Estonian Informatics Centre, 1997, para. 1). The open or modernising government movements have embraced ICT as a way to integrate policy in otherwise disparate fields, and through devices such as a ‘Citizen’s Charter’ clarify the services available and their cost structures (Cabinet Office, 2003). In education this rationale resonates with equity arrangements used to ensure all students have a fair and socialising upbringing. In the analysis of policy documents, the social impacts of ICT were components in the teachers’ personal skills (see Table 9 in section 4.2.1.2.1) for Estonia and the USA, and for all three countries in respect of student skills (see Table 12 in section 4.2.2). The analysis therefore shows that the social rationale is part of policy thinking in all three sample countries. It is also seen as important to policy in Australia as a pre-requisite for participation in society (Kearns & Grant, 2002, p. 11). This importance extends to the literature on lifelong learning and learning communities which promote social cohesion, and addresses solutions to the digital divide (OECD, 2000, p. 4; Hutta, 2002).

5.2.1.4 Economic rationales

The economic rationale appeared to be the most significant currently because of ‘knowledge economy’ strategies, and was shown in this study to embrace three distinct objectives. These comprised: generic ICT skills for all fields of work; more specialist IT skills for the production of ICT products and services; and also the need for economic efficiency within the education system itself. There is some concern amongst teachers that this new area of study is being imposed throughout school education without sufficient preparation or justification. Whilst schools do address specific workplace competencies in the latter years of compulsory education through vocational education programmes (Queensland Government, 2002, p.7), the application of this approach from the earliest ages is in conflict with a general teacher culture of student empowerment and life preparation (Nuldén, 1999, p. 3).

Australia is implementing a pilot scheme testing student readiness to use ICT in the workforce from Grade 3 onwards (Varghese, 2002, p.2) which relates to the first objective in the economic rationale. Such schemes can appear to be impositions for which teachers are not ready (BJ29, BM26, KB19) and support the view that “schools are losing their monopoly on learning” (Hargreaves, 1997, p. 6). This objective within the economic rationale is seen by some teachers as a potential threat to their autonomy and emotionally unsettling, especially in the context of nationally centralised standards (KN83) implemented through self-managed devolved budgets.

The more specialised skills within the second objective relating to expansion of the ‘knowledge economy’ are only just beginning to receive particular attention. One example is the emergence of Victorian Information Technology Teachers' Association as a break-away professional association to specialise on IT disciplines alone, distinct from the ICT across the curriculum focus of its predecessor body (VITTA, 2003).

The study found that the first two objectives within the economic rationale were not supported in the case of Australia because students do not acquire ICT skills at school (Meredyth et al., 1999b), and Australia has a large external trade debt in the ICT product sector (Australian Computer Society, 2002). The other possible economic advantage relating to the third objective, that of providing adequate teaching capacity within a restricted budget, has not received much public airing except in a few cases (Barber, 2000) or where there is an acute shortage of classroom places (McNulty, 2002). However, as was established in the literature review, the aging of the teaching workforce (Box, 2000, p.4; National Center for Education Statistics, 2000, Table 70) and the perceived relative cost advantages of ICT (Jurgensen, 1999, p. 16A) are no doubt significant factors in the minds of policy makers. The emergence of national policies for ‘the knowledge economy’ is a relatively recent phenomenon which has changed the direction of pre-existing policies for ICT in education (OECD, 2001b, p. 100). The consequence has been a considerable dislocation of initial focus and a weakening in implementation, especially in the face of competing curriculum reforms (SP26).

5.2.1.5 Lack of policy cohesion

The existence of the three rationales and their relative weight over time has generated considerable policy uncertainty in the area. The English national curriculum illustrates this well, with the first version incorporating ICT as a sub-section of the Design and Technology subject area (economic rationale), the second identifying it as a separate subject to be addressed over all the other subjects (social rationale) and the most recent raising it to a core subject with cross-curriculum application (pedagogical rationale) (Qualifications and Curriculum Authority, 2002). This lack of policy cohesion has done nothing to make teachers secure in the belief that ICT has a place in the classroom. The data illustrated the way policy makers resolve this diversity, by framing ambiguous objectives which appeared to the proponents as representing each of their diverse views (NM50) or by formulating standards at the lowest common level (DM67, 82). National policies for ‘the knowledge economy’ were becoming more important, but as they were implemented at local school level there were conflicts with other educational priorities such as the emphasis on group instruction for basic numeracy and literacy (BM147) or the need to closely supervise children’s use of the internet for fear they should encounter undesirable material (see for example South Eugene High and Tadcaster Grammar). Difficulties are caused by sending mutually contradictory nationally developed policy aspirations into schools. Teachers are confronted with equally compelling exhortations to utilise the power of the internet to internationalise education, but also reminded not to leave students unsupervised in case they encounter inappropriate material (. They are encouraged to individualise learning using ICT, but commanded to ensure group performance on national tests of literacy and numeracy is assured though whole class instruction (BM143). Other areas of policy conflict reflecting tensions between national and school levels included conservative restrictions in high stakes examinations and inertia attributed to adherence to pre-existing curriculum documents (Plomp, Anderson & Kontogiannopoulou-Polydorides, 1996, pp.11 & 17; OECD, 2001, p.13; Eurydice, 2001, p. 19). Both of these created considerable barriers to ICT adoption in the secondary school area (DM82). The existence of national curriculum requirements in England led to some highly faithful implementations (MR19), but at the cost of creating barriers to the cross-subject fertilisation ICT facilitates (see Tadcaster Grammar).

5.2.1.6 General trend is towards integration

The communication of policy is an essential part of implementation (NM198; Adamo, 2002, p. iv). There was a considerable lag between the development of policy in the USA and its adoption by schools and districts (Russell, 2000) as well as other examples where linkage to national policy was weak or unacknowledged (as in Theodore Roosevelt Middle, USA). Documents to facilitate this communication were useful, with the importance of exemplification materials stressed in England and the USA (NM182, 202; Thomas & Bitter, 2002). Despite the importance of such communication methods, the analysis of policy documents confirmed previous literature that the general nature of policies for ICT in school education has been predominantly focused upon integration of ICT into current classroom practice (Plomp et al., 1996; Bingham, 2000). This emphasis on supporting the existing curriculum with ICT was particularly strong in the USA (see section 4.2.1.3 on p. 96). Those involved in the development of policy (the expert panel) and others (Knezek, Miyashita & Sakmoto, 1994; Plomp et al., 1996) were critical of the poor current use of ICT in schools, and indicated that much more could be achieved, particularly through the development of new subjects and the use of ICT to cross disciplinary boundaries.

Previous research has been confirmed or extended in the response to Research Questions 1a and 1b which emphasised the current focus on integration and described the way in which national ICT policy comes into conflict with other policies at the point of implementation. The implication is that rapidly changing technology necessitates a frequent re-visiting of policy; and that the considerable lack of policy cohesion in this area is due to this and the multiplicity of rationales behind it. This lack of cohesion calls for the construction of an agreed and future-proofed framework for ICT in education since there is no agreed model at present (NM28).

5.2.2 Research question 2

Research Question 2: How have government inputs such as ICT frameworks, targeted funding and accreditation requirements influenced the use of computers in schools?

5.2.2.1 Types of government input

Curriculum documents provided from national level government had a significant impact on the way ICT was used by students in England and Estonia (BM8/10; EM62), but less so in the USA (DM23). Apart from the policies previously examined, and professional development structures to be looked at in Research question 3, the other major government input was infrastructure resources (UNESCO, 2002). These were often provided through targeted funding, as used by the federal department of education in the USA which promoted ICT equipment support at a level four times the general rate (see the background information for the USA on p. 287), sometimes derived from social equity programs such as Title 1 (DM4). The quality and connectedness of computer workstations, compatibility within an institution, perennial updating of a proportion of the stock and availability of networking were issues (KM6). In some cases computers were of a range of ages, some so venerable that Internet software was not available for them (for example at Tadcaster Grammar). It was found that the disposition of computers within a school was an important consideration for most of the case study schools, having a major effect on what they were able to do with ICT (see p. 104). This study did not examine in detail the extent of internet connections in the case study schools, but there was a range of bandwidth available per capita from the 1Mbit/s for 1000 students at Lyceum Descartes to 64kbits/s for 1436 students at Tadcaster Grammar. The level of infrastructure inputs was deemed by the case study respondents to have a very significant impact on possible curriculum frameworks for ICT (see Couth Eugene High; TE54,). Access to the internet sometimes came into conflict with protective behaviours policies, and student access to inappropriate material on the Internet was a concern (BJ2, KM50). In some cases, local rules about this had disabled the TCP/IP stack (internet connectivity software) on half the school workstations (see South Eugene High case study).

5.2.2.2 The influence of government inputs

There has been a variety of relationships between government inputs and actual ICT use in schools which illustrate the need for defined minimum levels of equipment infrastructure and national policy homogeneity. In Estonia, where a mandatory ICT requirement applies (see Appendix 6.8.6), equipment levels have been too low to permit schools to achieve an integrated approach across the curriculum (TE54). Low infrastructure levels have also been identified as the reason why students spend limited time using school-based ICT (Knezek, Miyashita & Sakamoto, 1994; Plomp et al., 1996; Harrison et al., 2000). These limitations may have led to the minimalist current use of generic office applications deprecated by expert panel members (DM60; NM64). Other studied countries had better infrastructure provision but in some cases have lacked a clear policy approach informing teachers about the purpose of ICT.

Policy cohesion is not easily achieved. In Australia national policies are negotiated through the MCEETYA process, requiring consensus between all States and Territories (Wenn, 2003, p. 19). Where there are no mandatory ICT student curriculum requirements (e.g. Australia and USA), adoption has often depended upon individual change agents for whom the reward is intrinsic or through the improvement of class discipline gained by greater motivation (Rogers, 1995, p. 19; HB at Applecross Senior High).

In England there has been a great deal of fidelity between policy requirements and school implementation for the mandatory ICT curriculum (CI 69, 71, 81, 99). However, this has been fragmented between different subjects, and so far lacks a coherent approach (NM34). Selwyn (1999, pp. 81-82) attributed the subsequent lack of success of ICT in UK schools to its policy ‘shotgun’ imposition through purely technology resource supply or functional terms instead of alignment with educational objectives. Fullan (1992, p. 29) concurred, emphasising the need for policy to clarify the meaning of change for those involved, culminating in new beliefs and understanding. Both authors emphasise the difficulty of achieving these new attitudes when policy is predominantly concerned with the supply of technology resources. Selwyn (1999, p. 85) also attributes policy failure to “the isomorphic structure of the school ... still rooted in industrial society”. This kind of structure where all the students in a class undertake similar activities at the same time does not fit an innovation ideally suited to individualisation and timetabling flexibility. Integration of ICT into traditionally structured schools is therefore difficult. This mismatch between adoption context and proposed innovation inhibits a transformative alternative or new business model.

The choice of integrative or transformative approaches may be a matter of timescale. Selwyn counselled policy makers to address “the quality, not the quantity, of the integration of computers into the school curriculum” (p. 87). Some people believe such an integrative emphasis will eventually transform the curriculum (BM 75) and “help solve inter-disciplinary problems” (DM 81). Other members of the expert panel asserted this transformation was already evident (KB 195). The implication is that successful adoption will depend upon all the critical success factors previously identified for ICT in education, as well as a policy view which embraces a transformative rather than an integrative perspective.

5.2.2.3 The tendency for collapse to generic office applications

The expert panel believed that one consequence of the policy focus on integration had been the contraction of ICT use in schools to generic office software (KB107; NM132; MR123). There was a considerable shortfall in expectations, as found in a doctoral study in the USA, with students using some word processing or rewarded for good behaviour with computer games (DM60). Because they had more flexible timetabling and fewer accountability requirements, primary schools were more able to exploit ICT (TE128). This was in contradiction to the finding in the literature that ICT can increase learner autonomy where this is a pre-existing part of classroom practice (IAEEA, 1999).

5.2.2.4 Schools’ own initiatives

Individual schools were introducing ways of using ICT in new ways unsupported by policy guidance. These approaches included greater authenticity in teaching materials through the use of contemporary images in student project work (WL at Applecross Senior High), the incorporation of self-paced interactive tutorials (HB at Applecross Senior High and KF at Theodore Roosevelt Middle), and student collaboration in international problem solving activities (DM2 at Theodore Roosevelt Middle, USA). These new approaches agreed with the finding from the literature that ICT can increase student-directed learning (Woodrow, 1999). Other school-initiated exploratory activities included the use of wireless networking for internal mobility (at Applecross Senior High), and for inter-campus connectivity (at Winthrop Primary and Lyceum Descartes). School-based development to support administrative functions and enhance links with the community included the third-party portal proposed at South Eugene High. Individual school-based change agents (as VT in Pärnu Nüdupargi Gùmnaasium) showed signs of a transformative approach to education in that very traditional context. However, teachers in the case study schools reported little incentive to pursue such transformative uses of digital materials other than the intrinsic rewards of greater student engagement or easier classroom management (e.g. HB from Applecross Senior High, Australia).These initiatives were proceeding without policy mandates or guidance, and illustrated the way in which the rapid rate of change was facilitating such experimental projects. Major changes were anticipated at Applecross Senior High, as the school contemplated the form of its next consolidated digital repository for curriculum and library materials in a user-aware way. In these cases the use of ICT was causing a re-think about the way information flows within the organisation could take place.

5.2.2.5 The growth of home computers

Student home computers were emerging as important tools for off-site learning and access to school resources out of hours (see Applecross Senior High; KM8, 50), thus extending the Australian literature (Meredyth et al., 1999b) to other countries (see Lyceum Descartes case study). School-level policy and implementation mostly ignored this higher availability of ICT in student homes (see Table 14 in section 4.4.1), with none of the case study schools having a developed local policy in this area, except floppy disks from home were allowed at Applecross Senior High (KM50). Despite this lack of policy, schools were pursuing activities which facilitated computer use at home, with most work word-processed: “Even though it is not stated, virtually everything is done on computer” (KM60). Reasons given by teachers for not incorporating home ICT into their practice included equipment incompatibilities and the perceived inequities of student access to computers and the internet at home (SS20; BJ34; SP58). As the digital divide has rapidly diminished for families with children (Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2000d), the equity argument has become increasingly untenable (CI65), but teachers in the case study schools have yet to be convinced to incorporate home computers into school education, citing the relatively high cost of a new computer (CI63), the difficulty of accessing one in a public setting, and incompatibilities of equipment as reasons to continue to ignore them outside school (for instance at Applecross Senior High).

5.2.2.6 The growth of CyberSchools

Several examples were found where transformation was taking place on a broader scale, such as virtual schooling in the pan-European Virtual School (European Schoolnet, 2000), the growth of virtual schools in the USA (Russell, 2003) and integration of home and school-based learning environments (Department for Education Training and Employment, SA, 2000; Foreshaw, 2000; Mitchell, 2000; Clark, 2001). The CyberSchool in Oregon (described in the case study on South Eugene High) provided a greater range of curriculum opportunities for students without having to leave their neighbourhood school (Layton, 1999). Such ICT-mediated communication deriving from online learning materials has benefits for students by allowing them to access a wider range of courses than would be possible with limited staff numbers and timetabling viability restrictions within a single institution. These government inputs have broadened to include electronically mediated supports for teachers through agencies such as the National Grid for Learning in England (MR185; NM182) and the ‘Free’ web-site in the USA (DM9).

The answer to Research Question 2 has revealed there is little agreement locally which substantiates the pedagogical rationale. Many schools are implementing government supported ICT programs with difficulty. Equipment sufficiency, conflict with other priorities and lack of extrinsic rewards for teachers were all found to have a bearing on the way in which computers were used in schools. In a growing number of cases there are non-school based government programs to expand ICT in k-12 education.

5.2.3 Research question 3

Research Question 3: What teacher professional development policies and procedures were evident in the countries studied?

5.2.3.1 Pre-service and in-service ICT operational skills focus on integration

Policies for teacher ICT professional development were generally focused on operational skills, in fact, if not in principle. This level of expectation was explicit in Estonia, where the International Computer Driving Licence (Australian Computer Society, 2002b; see Estonian ICT requirements for teachers in Appendix 6.8.5) was the national training standard (TE136, 138). Much of the national NETS framework in the USA was based upon generic office applications, although classroom practice was expected to go beyond such tools. Policy in England had also provided a national training scheme targeted at ICT integration into teaching practice through a large lottery-funded professional development project which presumed and required teachers to have basic operational ICT skills as a foundation (BM38). This program was providing differentiated training to every in-service teacher to the same standard as required for new teacher education graduates. However, a sample benchmark test for the latter was predominantly concerned with mastery of generic office applications (Teacher Training Agency, 2002), putting it at a similar level to the Estonian objectives. It was generally the case that standards for in-service teachers were very similar to those for pre-service teachers (DM33; MR191, 195; KB11) and were mainly mandatory (see Table 8 in section 4.2.1.1). The focus on the mastery of generic office applications appeared to be linked to the policy focus on integration. This could be seen as a confidence-establishing preliminary state, but since micro-computers have been in schools for nearly 25 years, perhaps one that has been tried and found unfruitful.

5.2.3.2 ‘Ownership’ as an element of teacher ICT professional development

The literature had identified ownership and relative advantage as the most significant factors for innovation adoption (Clayton, 1993; Parker & Sarvary, 1994). Ownership in the sense of innovation arising from within an organization was interpreted and implemented through personal equipment schemes. There was evidence of computer ownership schemes for teachers as an adjunct to professional development in some states of Australia and throughout England (National Grid for Learning, 2002; OFSTED, 2002, p. 3; State of Victoria (Department of Education & Training), 2002; Becta, 2003) and this was confirmed in case study schools (see Applecross Senior High and Winthrop Primary, Australia). However, the expert panel members considered that there was a considerable lag between technological advancement, student uptake of ICT skills, and teacher readiness to utilise these (EM1).

5.2.3.3 The amount of professional development required

The amount of time teachers need to become familiar with ICT in the literature was estimated at nine hours per year (Smerdon et al. 2000) and should take about 30 percent of the ICT budget (Byrom, 1997). This was confirmed in the study where 40-50 hours of initial training were expected (see p. 309 in section 6.10.6), and the expert panel deemed 12 hours of professional development required per year to maintain currency in the face of continuous software upgrades, taking 15-30 percent of state ICT funds allocated to ICT (DM84). The aging of the profession and difficulties with recruitment (see p. 59 in section 2.6.1.2) makes it difficult to provide the time teachers need for professional development in ICT. These additional factors are accentuated by the constant revision of generic office software used as the basis of much teaching and compounded by the frequent emergence of additional innovative equipment. To extend teacher knowledge to subject-specific innovations requires yet more teacher time. Training in the application of subject-specific software, which has a range of non-standardised controls, makes the whole area highly problematic. This is a very different situation to most business applications of ICT which expect the user to operate one program for considerable periods. By contrast, teachers and students normally expect to cover a wide range of curriculum areas and content over a 12 week period. One emerging solution is to package access to a catalogue of ‘learning objects’ accessible through a standard web-browser, which minimises the training required for individual teachers (The Le@rning Federation, 2001; Learning and Teaching Scotland, 2003).

5.2.3.4 Assessing the effectiveness of teacher ICT professional development

Several ways of assessing the effectiveness of ICT professional development have been proposed. One metric in the previous research observes actual teacher use of ICT in classrooms (Bender, 2000). The expert panel suggested the criterion for successful ICT professional development is the subsequent quality of teacher decision-making (KB137), and that it should be done using authentic situations (TE148). Another way to evaluate this is to look at subsequent curriculum changes (EM89). This method opens up a whole raft of important issues because it suggests the traditional curriculum cannot be used as the yardstick of successful teaching with ICT. There are several accepted ways to assess student learning outcomes in respect of ICT use, and these are now examined.

5.2.3.5 Lack of alignment between teacher and student ICT standards

Student ICT learning outcomes can be assessed using the standards produced as part of national policies and examined in the Results section of this thesis. In the ICT area, teachers are typically being trained in tandem with their students: not a normal state of affairs since teachers are in most other respects fully trained at the start of their appointments. Consequently, skills standards for teachers and students are being produced simultaneously in each of the sample countries. In the centralised system of England, these sets of standards were the responsibility of different government departments (KB11), and it was asserted that the standards were out of alignment with each other (KB163). This extended previous literature which had been silent on the issue of alignment. The alignment issues in the findings were particularly identified in respect of the difference between what students were expected to learn about ICT and what teachers were expected to teach. This discrepancy due to lack of inter-departmental liaison did not apply in the USA since the ISTE organisation was the proponent of both student and teacher standards (International Society for Technology in Education, 1996 & 1998); but nonetheless teacher ICT skills appeared to have been considered independently of student ICT skills and many teachers cannot themselves achieve the student standards (DM17-18). This divergence at the policy level is then left to resolution at the school level with a great diversity of consequent approaches. It also explains the crucial nature of individual change agents, most of whom are teachers (see for example VT in Pärnu Nüdupargi Gùmnaasium, Estonia). The question of alignment also extended to the relationship between teacher professional development and strategic priorities (Downes et al., 2002). How alignment might be achieved is beyond the bounds of this thesis, but the issue has been identified and explored here.

5.2.3.6 Assessing ICT by student learning outcomes

Another way to assess student learning is to use non-ICT specific curriculum frameworks as in the literature on ICT effectiveness which uses meta-studies to compare learning outcomes with, and without, ICT (Sinko & Lehitenin, 1999). Perhaps the most important point to make here is that ICT appears to be flexible enough to support these existing curriculum frameworks about as well as other innovations (Parr, 2000). ICT also appears from the descriptive research (McDougall, 2001) to be able to foster new ways of learning about new topics, but there is insufficient literature exploring this idea (OECD, 2001; Venezeky & Davis, 2002, p. 35). Therefore the pedagogical rationale examined in Research Question 1 stands upon a base which assumes a curriculum which has not changed to accommodate new learnings and new ways of learning. Furthermore, there are implicit resourcing issues here because the cost of providing and maintaining the currency of ICT infrastructure in schools appears to be a major factor inhibiting good use (OECD, 2001, pp. 16 & 93; Eurydice, 2001, pp. vii & 17). This would appear to be supported by the discrepancy between home and school equipment levels (see Table 14 in section 4.4.1).

The response to Research Question 3 is therefore one which identifies existing ICT professional development as focused on operational skills for integration, with some examples stimulating teacher computer ownership. Relative advantage of ICT is about as good as other innovation in education, but there is a lack of alignment between teacher ICT professional development, national strategic purposes and ICT standards for students.

5.2.4 Research question 4

Research Question 4: In the light of the preceding research questions, is it possible to describe the use of ICT in schools within a particular framework which indicates future directions?

5.2.4.1 Findings from the previous research questions

The answers to the previous research questions have shown that there is a need for an agreed framework for ICT in school education, prompted by the growth of home access to computers and of cyberschools, the lack of policy cohesion in the area and the questionable validity of using pre-existing curriculum outcomes to assess student learning acquired through ICT. Such a framework would have to address the difficult policy areas of home-school ICT relationships and currently low standards of ICT use.

Whereas national and local policies focus on integration, schools are comparative computer deserts compared to students’ homes, despite considerable government ICT funding of £2.7 billion per annum in England for example (Department for Education and Skills, 2002). This disparity in equipment was rarely recognised in school policies or by teachers. In addition, some experts were critical of the relatively low expectations of ICT in schools, comparing current activities such as word processing with the capacities of equipment to predict weather for large geographical areas (DM82). Once again, this is despite considerable government resources being put into teacher professional development (New Opportunities Fund, 2002; BM27).

5.2.4.2 Possible ways to resolve these difficulties

The literature review established that rapid changes in the underlying technology underpin these challenges for decision-makers in the public policy arena (Moore, 1997; Carrick, 2002). Theoretical responses vary from the rationalist liberal capitalist approach for strictly hierarchical governments, through the ‘satisficing’ art of compromise (Simon, 1993) to the muddling through incrementalism of Lindblom (1959). Whereas an incrementalist view would make small changes in policy, the study has identified major differences between leading and laggard institutions. There is evidence that current approaches to policy are not sufficient (Papert, 1993; Holmes, Savage & Tangney, 2000, para. 3.1; OECD, 2001, p. 112) because ICT is leading to fundamental changes in curriculum. Therefore major policy changes may be required to meet the challenges identified above. Previous studies had suggested that undesirable consequences of innovations cannot be minimised (Rogers, 1995, p. 11-1). This aspect has been little studied in the area of ICT in school education and existing models of stages of development have largely ignored it (see for example Kraver, 1997). However, the story of ICT in education is one of the struggles of teachers to do just that. This study has described some of the efforts that individual teachers have contributed to their students’ successful and innovative use of ICT.

5.2.4.3 The possibility of building a new framework

The development of a particular framework for ICT in school education needs to be grounded in the experiences of teachers and policy makers to ensure a more faithful adherence to practice in the description of current practice and expectations for the future. Previous frameworks explored in the literature review have been developed largely without such a link to an international data set. The literature set the parameters for any future framework: it should apply to a range of audiences (Dwyer, Ringstaff & Sandholtz, 1991; Dwyer 1994) and be based upon the capacities of existing ICT equipment (Kraver, 1997; Valdez et al., 2000). It could also link to national ‘knowledge economy’ strategies (Caldwell & Spinks, 1998). The study found there were expectations and examples of transformation of school education as described by Heppell (1993).

This transformative view is compatible with the work of Perkins, Schwartz, West and Wiske (1995) who, in reference to ICT in mathematics teaching, stated that “changes in degree, helpful though they might be, simply are not enough” (p. 89). They examined uses of technology that “foster changes in the nature of teaching and learning, not uses that only improve the efficiency of what was done in the past”. It was found that although policy was generally focused at the integrative stage, policy-makers at national and school level were expecting and implementing new uses of ICT which were changing the educational process. An important element of this was the incorporation of student home computers as a learning tool. Therefore it is reasonable to conclude that a particular framework can be devised which may indicate transformative future directions, and which also fits both the constraints learned from previous models and the data from this investigation.

5.2.4.4 Examination of three propositions for ICT in education

In the derivation of a model accurately and usefully describing the stages of development of ICT in school education, three competing propositions were suggested from previous research and the results of this study. The determination of which of these propositions is supported by the evidence depends upon the plausibility of interpretations for each, and the empirically discovered relationships between interpretations and theories (Popper, 1957, p.131; Smith, 1975, pp. 275-276).

The ‘bubble burst’ proposition: that ICT in school education would increase and then decline into very limited use, as other technologies have done in the past (Costello, 2002).

The integrative proposition: that ICT in school education would increase and then plateau at a particular level of use. This proposition could be developed further to determine the kinds of use, whether as a separate subject or spread through other curriculum areas (Department of Education, Training and Youth Affairs, 2000, p. 11)

The transformative proposition: that ICT in school education would continue to increase over the foreseeable future and transform both existing curriculum subjects and the nature of the teaching and learning process (Nichol & Watson, 2003, p. 133).

The bubble-burst proposition suggests that ICT in school education will follow the path taken by information technology stocks and shares in the year 2000, when the Nasdaq computers index fell by over 70% of its peak in a period of twelve months. It is unlikely in the prevailing policy climate that this will happen to ICT in schools education, and in fact demand for ICT goods and services climbed through the ‘tech-wreck’ period (Matsuo, 2003). It would be quite unusual for the education sector to become independent of a class of innovations affecting almost every other area of society, especially homes (Di Gregorio & de Montis, 2002; OECD, 2002b). This proposition is therefore not accepted on the evidence available at present.

The integrative proposition reflects the current policy thrust (Plomp et al., 1996; Bingham, 2000). As shown in the discussion of Research Question 1a and 1b, this proposition stems from a focus on the economic rationales and is synonymous with a focus on generic office applications and teacher professional development aimed at operational skills. The sustainability of this integrative state therefore depends upon continued satisfaction of its resourcing requirements and lasting policy commitment to the supporting rationale.

The transformative proposition has been considered in the light of evolutionary and revolutionary transitions (Nichols & Watson, 2003, p. 133). There is policy pressure for such an approach from the members of the expert panel in this study, who regarded current use of ICT as “mundane” (see for example DM20, DM46). Additional support derives from the case studies, for example the CyberSchool discussed at South Eugene High, the Miksike collaborative web-site at Descartes Lyceum and the use of interactive mathematics web-sites at Applecross Senior High, each of which demonstrates the use of ICT to enhance off-campus learning. The transformative proposition suggests that standardised tests using traditional measures may be inappropriate when ICT is a significant feature of learning (Fouts, 2000, p. 27).

Both the integrative and transformative propositions can be accepted on the basis of existing evidence. The consequence is to determine whether they are alternatives existing side by side, or whether they are ordered with one proceeding the other for a given school or system. A grounded theory approach was used to develop a model to explain the way in which these two propositions could interact.

5.2.4.5 Connecting the categories with a logic diagram

The researcher became theoretically sensitive through the extensive literature review, professional work in the field, data collection and analysis. Therefore it was possible to categorise the material from the study, assign properties and dimension them. These analyses are presented in Appendix 6.13. Open coding (Corbin & Strauss, 1990, p. 12) was carried out until theoretical saturation of the categories was achieved (Glaser & Strauss, 1967). The categories were connected with their contexts, strategies and consequences, through axial coding. The core category of ‘model of development for ICT in school education’ was chosen because of its centrality between ‘policy making’ and ‘implementation and practice’.

In a grounded theory approach, the logic diagram brings together the findings of the study and the literature. It shows the cycle of policy generation, implementation and evaluation (Jenkins, 1978, p. 17; Bridgeman and Davis, 1998, p. 24) as found in the area of ICT in school education. Policy generation has been shown to respond to three rationales, the economic flowing from ideas of the ‘knowledge economy’, the social and the pedagogic. The pedagogical rationale is dependent on operationalisations of ICT effectiveness (McDougall, 2001). Policy is mediated through an implicit or explicit model of stages of development to drive implementation through the curriculum. This implementation and practice is dependent upon equipment, connectivity and digital materials such as application software, databases and online teaching resources. Student learning outcomes are the result of this implementation and practice, and there are difficulties with alignment of these (actual or desired) and teacher professional development. The outcomes are affected by student home access to ICT, but this is rarely a component of policy generation at national or local school level. A logic diagram was constructed which illustrates the connections between the conceptual categories found in the study (see Figure 6).

Figure 6: Logic diagram of relationships between concepts

5.2.4.6 Development of the proposed model

The study methodology made use of multiple methods and collected data from multiple sites and persons to eliminate interaction effects found in other studies where sampling has been affected by treatment bias (Good, 1972, p. 373). Both the literature review and the data indicated that current practice is relatively poorly regarded, and has much potential for improvement. Some individuals and some systemic initiatives have moved on from the integrative phase. Therefore it is necessary to extrapolate from the observed trends and see what these leaders are doing as they try out new ways of working without policy guidance. The consequences of a transformative stage are being explored in local situations as schools experiment with the possibilities of the new technologies.

The proposed model had to match some very specific requirements which were identified in the literature review (see section 2.5.1 on p. 56). For the model to be useful, it had to be sufficiently general to accurately describe the situation well, yet be simple enough to avoid over-complexity. This meant the model had to describe a minimum number of developmental stages to match the evidence, yet not include Heppell’s superfluous stages. The other requirements were derived from the open coding analysis, and included application, generalisability, validation, assumptions and alignment. The property of application required the model to cover as many school sectors and age groups as possible. The model was validated against a diverse range of school situations in the case studies, which had been drawn from geographically diverse areas. Alignment could be demonstrated by using the model as a starting point for development of future teacher ICT professional development and student learning outcomes.

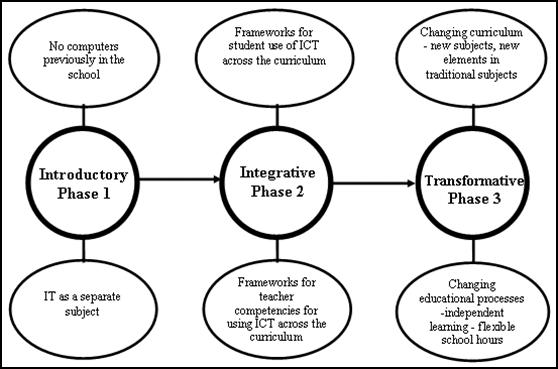

From the data, the open coding analysis, logic diagram and the literature, a proposed model was constructed to describe stages of development for ICT in school education. This outlines three stages of development; the introductory, the integrative and the transformative (see Figure 7):

Figure 7: A general model for the development of ICT policies in schools

5.2.4.7 Characteristics of the model

The introductory Phase 1 corresponds to the period where the school, system or participant meets computers in education as a subject to be studied. This would cover contexts where ICT was an examination subject or was only studied in terms of operational skills. The integrative Phase 2 describes contexts where ICT is incorporated into the teaching of other subjects, and is included in teacher planning. However, there is little or no change to the curriculum or the learning outcomes expected of students. The transformative Phase 3 makes no assumptions about the place or timing of learning, and includes contexts where topics studied include those that are not possible without ICT.

This model was further developed to establish levels of particular attributes for phase transitions by extracting from the data details of student use of ICT, ICT professional development for teachers, school implementation (including frameworks for student ICT learning outcomes) and government intentions/philosophical approaches. The levels of similarity and the overlaps between practices in the different case study countries contributed evidence for the three-phase model. Even though the political pressures and the educational administration arguments used to justify ICT developments in schools in each country visited were different, there was consensus about the overall direction in which these developments would take students.

These issues and observations from the case studies and policy reviews were incorporated into the consolidated table (Table 34) which gives values for transition from each Phase to the next. The critical values derived for the development of the model relating to student use of ICT reflected the degree to which home access to computer and the Internet were available. Since younger students generally had less access than older ones, a medium value on age of 11 years was set in the comparative table of Phase transition indicators in the Table. As the Phases overlap, the headings indicate the transition using a slanting line. Attributes within a Phase also vary, and this is shown by separate columns for the starting and consolidated values divided by a dotted line. Thus the initial school and home workstations for the integrative Phase 2 were 486 PCs (typically) but through a process of maturation and technical development, multi-media computers were more representative by the end of the Phase.

The proposed three-phase, two-level model for the stages of development of ICT in school education resolves difficulties with competing propositions in the area and is supported by policy documents, an expert panel and case study observations. It also overcomes the problems of models in the literature by using a multi-site, multi-method study with case study and literature analysis techniques. This current study is the only major research which has been conducted with a focus on the global transition of education from an industrial group-instruction stage to a post-industrial ICT based stage. While some locally-based planning guidance documents gave a series of stages through which a school might pass, none of these was based on country visits or an analysis of what was actually happening in schools around the world.

The new model requires interpretation for application to policy-making at national, regional and school levels. A central feature of Phase 3 in the model (see p. 136) is transformation in the way in which school education is delivered, with an expected increase in differentiation through the use of ICT-mediated flexible delivery for ‘independent learning’. More decentralised education systems were more conducive to this axial principle (Bell, 1973; Jones 1980, p.112). For instance, the centralised education system of Estonia had not considered ‘independent learning’ as part of the ICT curriculum framework, and was inhibited from broad implementation of transformative Phase 3 by low infrastructure levels. However, some ICT-based remote teaching was being done on purely pragmatic grounds to deliver advanced courses to students in remote locations. England also represented a centralised system which had adopted some ICT-mediated independent learning where deemed appropriate. Infrastructure was good, and there were a few examples of online learning. In the devolved context of the USA infrastructure was excellent, yet independent learning had been excised from the national ICT framework for students but was clearly evident in the case studies. Finally, the highly devolved Australian context had no national ICT curriculum framework, infrastructure was excellent, and there were many examples of ICT-mediated independent learning emerging.

Much evidence of the transformative Phase 3 can be seen in tertiary education, where 70 percent of USA institutions taught subjects by the Internet and about one in three had whole degrees taught that way (Lawnham, 2000). Examples of completely ‘virtual universities’ include international consortia such as Western Governors’ University (Western Governors’ University, 2000), Universitas 21 (University of Nottingham, 1999), Scottish Knowledge, NextEd (Richardson, 2000) and Boxmind (O’Reilly and Hellen, 2000). Competing with these commercial ventures are free, fully accredited university courses (SAATech, 2000; Vest, 2001) and open source online course management systems from a variety of reputable sources (OKI, 2002; Narmontas, 2003).

A final demonstration of the approaches being taken in transformative Phase 3 has been the response of textbook publishers. Some conventional text book publishers are now providing extension CD-ROMS and linking their normal products to complementary web-sites. The latter extend the content, provide updates and amendments, test understanding through quizzes and allow the publisher to advertise new material (Roblyer & Edwards, 2000, p. 251). Wiley is an example of a publisher that provides on-line courseware to teachers:

Aside from receiving robust, already developed e-packs, adopters of selected Wiley texts receive a pre-paid site license to use WebCT, 24-hour technical support, and password access to the Wiley WebCT Course [partnering the title] (Wiley, 2000)

These examples were no longer rare at the time of writing and represented a significant shift from printed educational materials to providing them electronically.

Providing advice for Australia in the field of ICT in school education was one of the main aims of the study (p. 14). This is done by applying the model to two states in the following section.

5.2.4.8 Application of the model

School curricula in Australia have been the responsibility of the individual states and territories forming the Commonwealth (Commonwealth of Australia, 1991). Common goals were agreed in 1989 (Ministerial Council on Education, Employment, Training and Youth Affairs, 1989) and revised in April 1999, establishing eight key learning areas. The key learning area of Technology incorporated the idea of ‘data’ as a raw material, giving students the opportunity to create information products. The curriculum developers and the writer of this study took the analogy that data + processing = information (Australian Education Council, 1994). This approach was at the level of the introductory Phase 1 of the model, since it facilitated the study of ICT for its own sake. Bigum et al., (1997) subsequently commented that development had almost stalled, not because of difficulties in accessing sufficient and powerful equipment, but because teachers in the main were unconvinced that deployment of ICT held educational value for students. While maintaining the equipment, and providing a continuous stream of training was proving problematic, teacher cynicism still formed a significant barrier to increased utilisation. Most pupil uses were unauthentic and for lower-order thinking skills, with most applications involving word-processing, rote learning, and simple information reproduction.

Development was revitalised when education and training were included in the Australian strategic framework for the information economy (National Office for the Information Economy, 2000). Federal action for schools was illuminated by a research project which strongly recommended the promotion of ICT integration into all teaching and learning (LifeLong Learning Associates, 1999), articulated in the school sector plan as “improving student outcomes through the effective use of information and communication technologies in teaching and learning” (DETYA, 2000b, p. 3). Running in parallel with these over-arching strategies from the Commonwealth government, state-based activity relating to ICT in schools was remarkably diverse. A summary article outlined the main characteristics of the many programs in progress at that time (Lelong & Summers, 1998). Additional state summaries were available from the Education Network, Australia (EdNA, 2000) web-site.

The proposed model is compared against two sample states, chosen for the differences between them, their representative nature, and the researcher’s familiarity with them.

5.2.4.8.1 Queensland

Queensland had a ‘Schooling 2001’ project (Lelong & Summers, 1998) which had five components, all designed to improve student learning outcomes through integrating computers in the curriculum. The five components were to provide technology infrastructure, develop staff IT skills, provide quality software, evaluate the effects of ICT on student learning outcomes and a marketing strategy to promote awareness of worldwide information resources. Among these strategies were some very specific teacher learning technologies competencies (Education Queensland, 1998) which were to be included in enterprise bargaining negotiations, with the aim of progressively getting accreditation for all teachers by the end of 2001. They built upon the Guidelines for the use of computers in learning (Department of Education, Queensland, 1995) which identified the main goals for students using computers. Students were expected to use computers for a range of purposes; namely to develop operational skills, develop and understanding of the role of computers in society, critically interpret and evaluate computer-mediated information, develop skills in information management and develop appropriate attitudes to the use of computers.

Queensland was revising school curricula through ‘the New Basics’ (Education Queensland, 2000). ICT was subsumed into the learning area of multiliteracies and communications, the others being life pathways, active citizenship and environments/technologies (p.43). The opportunity for transformation was expressed thus: “new communications change the way we use old media, enhancing and augmenting them” (p. 50). However, this has to be done in the context of preventing curriculum overcrowding and preserving traditionally important skills such as handwriting.

New Basics has an emphasis on locally produced operationalisation. It includes a panel of ‘Rich Tasks’ to demonstrate student competency and acknowledges a need to raise retention rates into Year 12 by some 20 percent. With such imperatives dominating the development of this new curriculum model, the issue of the way in which ICT has the potential to really modify the way schools work appears to have been lost. Certainly, there was a commitment to a Virtual School, but this seemed to be no more than a face-lift for existing distance education services. Therefore, although the strategy paper acknowledges that students will need new skills to understand and work within a culture permeated with new information technologies, the result is only at the level of the integrative Phase 2 of the model while holding out some opportunity for elements of transformative Phase 3 to emerge at a local level.

5.2.4.8.2 Tasmania

Tasmania has a history of support for ICT in school education dating back to 1972, notably through the Elizabeth Computer Centre (Bowes, 2001, p. 38). More recently, general ICT initiatives have been guided by a strategy paper which adapted the ACOT stages for students to define a progression through accessing, extending, transforming and sharing information (Freestone, 1997). Additional investment to overcome barriers to adoption has provided equipment, networking, maintenance, professional development, and the ‘Discover’ web-site (EdNA, 2000). The Discover site has been a key component in strategy, hosting a large range of OPEN-IT on-line learning materials (see http://www.discover.tased.edu.au/netlearn/courselst.htm), originally devised to support learning where specialist teaching was not available, but more recently hosting materials targeted at the bulk of grade 7/8 students in schools (Annells, 2000). This move from learning on the periphery to learning in the core marked a significant change, reinforced by ICT skills requirements in teachers’ job descriptions (Deputy Secretary (Corporate Services), 2000). Employment patterns were changing as school-based teachers and students participated in the state-wide ‘Discover online campus’, from which online courses were run without the need for co-location. This required special attention to school funding, which had previously been site-specific. Employer professional development still concentrated on operational skills, with only one of five modules for in-service teachers focusing on ‘integrating ICT into teaching and learning’ (Sigrist, 2000). Encouragement for ICT from the teaching profession has been quite explicit. The local branch of the Australian Education Union adopted a policy in 1999 that stated “students should be able to spend up to 20% of instructional time using modern computers” (Australian Education Union, 1999, p.1), three times that found in a local study (Fluck, 2000).

It is evident that many schools have used ICT in novel ways. Examples include a ‘travel-buddy’ project used to connect a Tasmanian school with three schools in Argentina (Duggan, 2000), benefiting from the commonality of the school year for southern hemisphere countries. A post-compulsory college (student ages 16-18) reported 20 percent of its teaching load was in the online courses, with half the 162 staff involved (Andrews, 2001). Flexible learning has contributed to at least one school adopting a nine day fortnight (Wade, 2002) and improvements for students who find school a challenge (Esk Express, 2002). A framework for integrating ICT into school education was adopted by many schools (Computer Education Discussion Group, 1996; Byron, 1997; Fluck, 1998). These activities point towards the integrative Phase 2 of the model with indications of strong preparation for the transformative Phase 3.

A summary of the progress of the other Australian states towards each of the phases of the model is given in Table 35. This study now concludes with recommendations for various elements of the education profession and for future research.

5.3 Recommendations

Recommendations from this study fall into two main groups: those for use by particular groups in the field of school education (E1 to E3) and those for future research (R1 to R4). Although particular audiences are specified for each of the first group, there are examples where concerted action is required by other actors for the recommendation to have effect. In particular, the issue of alignment between policy areas requires cooperation on a wider scale.

5.3.1 Recommendation for the teaching profession

E1: ICT professional development for teachers should be considerably extended, aligned with student learning outcomes, and encompass a wider range of ICT applications relevant to their area of teaching specialisation.

Data from Australia show that some accreditation authorities are requiring teachers to be able to use ICT and understand its role in educational practice (Board of Teacher Registration, Queensland, 1999, 6.11 & 6.29; Australian Council of Deans, 1998; Education Department of Western Australia, 1998, p. 6). Evidence from international studies shows the latter requirement is often an optional part of teacher training in Australia (Department of Education, Training and Youth Affairs, 1999a, 1999b). This may need to become a mandatory requirement, developed in line with guidelines established by the peak professional association (Williams & Price, 2000, pp. 6-41) and a recent investigation into current practice (Downes, Fluck, Gibbons, Leonard, Matthews, Oliver, Vickers and Williams, 2002). Competency standards for this have been explored (UWS, ACSA, ACCE & TEFA, 2002) but need to be aligned for those for students (see recommendation E3).

The strategy of facilitating teacher computer ownership appears to be a cost-effective way to maximise training opportunities. Teachers need to examine the evidence of ICT efficacy to assess ‘relative advantage’ (Clayton, 1993; Parker & Sarvary, 1994; Rogers, 1995), by visiting local centres of excellence, and having the time to become confident in their own skills. Many need to reflect on the equity implications of ignoring the full extent of home computer and Internet access by students. As the Education Department of Western Australia (1998, p. 6) put it: “Teachers will include the roles of facilitator and coach, while students will add the roles of mentor and teacher”. Although the Australian Teaching Council has disbanded (Williams, O’Donnell & Sinclair, 1997), this recommendation might be best addressed by professional associations working in tandem with systemic agencies.

5.3.2 Recommendation for teacher training accreditation agencies

E2. Systemic accreditation schemes for pre-service teacher training courses should permit a limited proportion of practicum or school experience to be completed in virtual classroom settings.

The study identified the growth of virtual schooling and the transition of this delivery mode from the periphery to the mainstream (Annells, 2000; Feeney, Feeney, Norton, Simons, Wyatt, & Zappala, 2002, p. 41). Given the growing importance of this mode of teaching, it is appropriate to suggest that pre-service educators are given the opportunity to generate online course material and supervise students who are using this in their learning. Most teacher education course include mandatory professional experience components, but regulatory processes rarely foster the acceptance of virtual teaching and timetabling pressures often exclude a virtual practicum alternative. As an example, pre-service teachers are required to undertake “not less than 100 days of professional experience, with a minimum of 80 days’ experience in schools and other appropriate educational settings” (Board of Teacher Registration Queensland, 1999, p. 17). Exactly 80 days of professional experience were included in the calendar of such an approved course (James Cook University, 2000). This recommendation to permit some limited professional experience in a virtual practicum endorses that of Downes et al. (2001, p. 80).

5.3.3 Recommendation for national decision makers in Australia

E3: In relation to curriculum, national authorities in Australia such as MCEETYA should consider existing ICT frameworks and determine whether adopting such a framework nationally would promote policy cohesion and alignment.

Previous work has been done in Australia on frameworks for student use of ICT (Australian Council for Computers in Education and the Australian Computer Society, 1995; ACT Department of Education & Training and Children’s, Youth & Family Services Bureau, 1996; ACT, 1997). However, these have not been used to generally focus and align policies for professional development and student learning outcomes in the way indicated as necessary by this study. There is evidence from the USA that federally adopted standards can be disseminated and implemented through the use of policy instruments such as targeted or tied funding like Title 1 or the E-rate (DM4). This recommendation endorses the suggestion that “a consistent approach within the school system … must cover how technology is applied within schools to aid the learning process” (Hogg, 2002). Such a framework should be communicated to teachers by using sector-specific exemplification materials and should be aligned with ICT standards for teachers (NM interview; O’Donell, 1996, pp. 121-126). Such a framework would need to include the ‘independent learning’ mode (Wood, 1998; Fitzgerald & Fitzgerald, 2002). Evidence from the case studies showed schools were adopting these techniques to broaden the curriculum and improve student management. Implementation of the framework needs to address school access to digital resources appropriate for the whole curriculum beyond generic office applications by using central brokerages or application rentals.

5.3.4 Recommendations for future research

The model of stages of development for ICT in school education developed in this thesis has, like all good research, raised as many questions as it answers. In particular there are matters of generalisation, verification and greater discrimination to be explored.

R1: This study could be extended by examining policy exemplification and communication material.

The main sources of data in this study have been national policy documents, and expert panel and school case studies. Although the national policy documents were easily identified, it became apparent during the research that they were regarded as subsidiary for the classroom teacher: “the statutory bit, the definitions, which I would have done in 10 point Courier” (NM192). In addition there were schemes of work and other exemplification materials which were considered more relevant to daily teaching (Thomas & Bitter, 2002). A comparative examination of such policy dissemination materials may provide data more grounded in practice.

R2: Further research should be done into the building of social capital and personal networks using current school resources, while academic learning is increasingly displaced into self-directed flexible delivery modes.

This study found growth in virtual schooling which can supplement school-based learning and support a greater proportion of independent learning. This may free time for exclusively socialisation oriented activities and there would be a good case for students to spend some of this time working in independent teams on projects seen as more relevant to themselves, where teacher leadership was expressed in a less-directive way. For example, West (2000) sees the future Australian student as one who may pick up social, sporting and cultural skills at a neighbourhood learning centre and combine this with some online tuition at home. Further investigation into a similar educational concept is being undertaken by Jolly (2002).

This line of inquiry can be seen as a section of social informatics research which has previously been scattered in journals of several different fields (Kling, 2000). Some of this work is particularly relevant to school education, and a discussion paper (Department of Education, Employment and Training (Victoria), 2000) looked at some of the social implications of on-line learning for post-compulsory students. Ten percent of innovations involved off-school sites, but significant breakthroughs were restricted by the constraints on school operations (Cuttance, 2001, p. 208). When learning through ICT (as opposed to learning with ICT), outcomes were broader than those specified in current curriculum frameworks. This debate about social and curriculum outcomes needs to be extended to examine the opportunities and difficulties for younger students, particularly when handheld wireless ICT increases mobility and convenience (Atputhasamy, Wong, Phillip & Chun, 2000).

R3: Study of barriers to the adoption of ICT in school education should identify ways to eliminate these.

Major barriers identified in this study were the lack of policies relating home and school-based ICT (Becta, 2002), and the lack of alignment between policies for teachers and students. These could be investigated using a series of case studies of schools where home access was brought to all students, perhaps using the ‘Tools for Schools’ model (Pennington, 1999, p. 37; Smithers, 2000). The study could be conducted using a multi-site cross national methodology based upon that of Venezky and Davis (2002). This would explore conflicts such as those found by Fitzgerald & Fitzgerald (2002) when independent learning systems in the Australian Capital Territory were not perceived by students as being supported by their teachers, despite the finding that student progress was much improved by the use of such systems. The proposed model can be used as an organising metaphor to classify the different approaches of schools.

R4: Research is needed into the future implication of ICT for curriculum reform.

The importance of the link between student outcomes and substantiation of the pedagogical rationale was identified in the current study. This link is subject to constant change because of the high rate of change of ICT (Moore, 1997). For instance, voice recognition systems deployed with common generic office products (Microsoft, 2003) could fundamentally alter concepts of literacy by increasing student writing speeds by a factor of ten (Fluck, 2000b). Speech activated language translation systems could have similar implications for foreign language teaching (Universal Translator, 2001). Yelland (2001) noted the need for curriculum reform in the light of ICT, supported by comments such as: “we are fitting new technologies into old curricula which were developed prior to their existence” (Kozma, 1994, p. 8) and “if technology makes it possible to teach difficult central concepts earlier and with greater understanding, then the traditional sequence of topics needs a complete overhaul” (Tinker, 1999, p. 2). This research could proceed through experimental studies following product-specific teacher professional development.

5.4 Endnote

The field of ICT in school education is maturing rapidly, and in the time of this study from 1999 to 2003 many changes have taken place. Virtual schooling has grown rapidly, becoming part of mainstream school education in many cases (Annells, 2000; The Le@rning Federation, 2001; Thomas, 2002) and a research topic in its own right (Clark, 2001). There is an urgent need to examine the effect of autonomous learning mediated through ICT using metrics of learning success that are not limited to conventional learning outcomes. The interaction between these two aspects may require a methodological innovation which it is hoped the model proposed in this thesis may facilitate.