Integration or

Transformation?

Integration or

Transformation?

A cross-national study of information and communication technology in school education

|

|

|

Chapter 3. Research Design and Methodology

3.1 Introduction

The main aims of this study (p. 13) included the exploration of national innovation paths in respect of ICT in education overseas and the provision of advice for Australia through a comparison process. It could therefore be classified as being located within the interpretive school of social science (Silverman, 1993), and a mixture of methodologies was appropriate. This chapter outlines the way in which the research approach was developed to ensure the data would be applicable to the Australian situation, and could be used in a predictive way (RQ4). The methods for each research question are introduced and a description is given of the research approach, sample selection and data gathering techniques. The validity, data analysis and limitations of the design are considered.

The iterative construction of the research questions was grounded in data collected from the field. Discussions with national level decision-makers frequently referred to policy documents, and it became clear that these were considered important statements intended to guide classroom practice. To study the way in which policies for ICT in school education were positioned in a country-specific context would have narrowed the research, so a cross-national comparative approach was selected (RQ1). As the study proceeded, the researcher saw a variety of practice in schools, indicating localised responses to national policy. This linkage was therefore examined in further detail (RQ2). In exploring these issues with teachers and relating the importance of change agents from the theory of innovations, the study also focused upon their needs and the way professional development addressed these (RQ3). Bringing these lines of investigation together into a coherent holistic framework was a major consideration of the study (RQ4).

The epistemological basis for the selection of methodologies to answer these four research questions was founded upon an empiricist view of knowledge (Hospers, 1973, p. 183). The paradigm or world-view (Kleinman, 1980) within which the study was conducted was characterised by a reductionist approach that assumes the existence of causality chains (Dufour & Renault, 1998) and the causal principle which underlies most scientific research (Hospers, 1973, pp. 308-320). The process of transmission from policy statement to classroom implementation does not permit strict adherence to such an experiential view, thus the assumption was made that if an innovation gains increasing levels of adoption, then there is a findable set of reasons why this may be the case, rather than accepting an ontological claim to existence a priori. This indicated an approach which identified data of events, people, objects and their interactions as the appropriate material upon which to base the analysis, but did not put boundaries on their immediacy to the innovation diffusion process. The extent to which the findings can be relied upon depends upon the immediacy of causes to effects; for there are many steps and confounding interactions in the journey from national policy statement to teacher activity in the local school classroom. Greater confidence can be expected for closely related steps in the process. The warrant for this choice of method largely depends upon a positivist view within a functionalist paradigm which attempts to interpret the phenomena rather than simply describing them (Burrell & Morgan, 1979, p. 26).

The application of this basis to research questions RQ1a & b and RQ3 (‘what’ questions) justified a quantitative approach using a positivist paradigm to identify the relationships between the variables. Given the possible number of policies for ICT in school education (at national, regional, school and classroom levels) and their nature, a strict quantitative approach was beyond the resource constraints of the study, so a limitation to national level policy documents was a restriction for these questions. In the case of research questions RQ2 & RQ4 (‘how’ questions) the use of a qualitative approach was indicated, using a phenomological/interpretive paradigm to discover the nature of the variables involved. The nature of these two research questions pointed towards an emic data collection approach, emphasising the importance of collecting data in the form of verbatim texts from informants to preserve the original meaning of the information (Pelto & Pelto, 1978). The details of the methodologies selected for each research question are dealt with in the following sections.

The research approach generated seven school level case studies, cross-national comparison of policies from three countries and involved 12 formally recorded interviews with experts, school IT coordinators and teachers.

3.1.1 Methodology for the investigation of policy (RQ1)

Policy analysis can be divided into academic policy analysis, where the link between policy determinants and policy content is examined, and applied policy analysis where the link between policy content and policy impact is investigated (Pal, 1992, p. 21). This study was concerned with both the generation of policy and its content, and therefore embraced both these kinds of analysis. Although policy can lead to legislation, this does not necessarily mean the policy is best examined through the resulting Act or other legislative outcome It is important to identify the appropriate documents for analysis, amongst the issue papers, executive summaries, journal articles, media releases and other instruments used for promulgating or translating policy into practice.

The process of investigating policy generation also needed to include the information available to policy makers, their own capabilities and expectations, and the tools available to them. Policy makers frequently use indicators and surveys as instruments to forecast the likely impact of policy, whether it involves action or not (Dunn, 1994, p. 198). A “policy model is useful and even necessary… [to] … distinguish essential from non-essential features of a problem situation” (Dunn, 1994, p. 152). The researcher had to select an approach that would identify the correct documents for constant comparison, and tools which would illuminate the underlying theories used by policy makers (Hogwood & Gunn, 1984, p. 18) as they generated the relevant instruments pertaining to ICT in school education. An appropriate approach was therefore to consult experts involved in policy making, and to identify policy documents which would facilitate cross-country comparison.

3.1.2 Methodology for the investigation of practice (RQ2)

The second research question sought information about the linkages between policy and practice based upon information about happenings in schools and the local interpretation of national ICT guidelines. The broad research approach required by RQ2 was one which would support the construction of theory based upon data gathered from the field to address the ‘how’ and ‘why’ rather than the ‘when’ or ‘how many’. The policy-practice relationships were outside the control of the researcher and therefore an experimental approach was not possible. A longitudinal approach based on a small number of sites in a single context would have provided useful data, but to effectively use the limited time available for the study a multi-national multi-site process was selected. However, a form of case study approach satisfied the requirements and limitations of the study.

Yin (1994, p. xiv) has argued that there are strong reasons for using a case study approach. It is the preferred technique when the researcher has no or little, control over the events (Yin, 1994, p. 1) and when the inquiry is into a contemporary phenomenon within its real-life context, especially when the boundaries between them are not clear (Yin, 1994, p. 13). Such a methodology is appropriate when the issue to be studied is not easily distinguished from its context, and there are more variables of interest than projected data points (Stake, 1995). As defined by Eisenhardt (1989), “case studies can involve either single or multiple cases, and numerous levels of analysis” and the method works well when data are collected from multiple sources of evidence, with data converging through triangulation (Lincoln & Guba, 1985; Jaeger, 1988). Merriam (1988) indicated the importance of the technique for this type of study, suggesting that “a case study approach is often the best methodology for addressing problems in which understanding is sought in order to improve practice.” This part of the research design incorporated ethnographic field techniques such as non-participant observation and semi-structured interviews as well as short direct observations.

Therefore the current study used a modified case study approach which gathered data in an exploratory way using constant comparison (Strauss & Corbin, 1998, p. 67) to build theory using several site visits and interviews to understand the perspectives of those involved. An iterative approach used a cyclic process of theory construction (Perry, Riege & Brown, 1998, p. 1955) and return to the field for validation or re-construction. This modified case study approach combined the observations and interviews with other data such as documents, systemic information about the school, examinations of student work and photographs to explore the variations in ICT policy implementation between selected schools. Initial discussions with national-level decision-makers were followed by visits to schools, providing an opportunity for comparison of the relationship or gap between policy and practice using a form of grounded theory. The cases were therefore situated in institutions and relied upon evidence based upon multiple sources of data (Gillham, 2000, p.21). Several perspectives were actively sought from at least the ICT coordinator and as many other teachers as could be observed and/or interviewed. The goal of the case studies was to identify critical factors in ICT use which reflected the origin of learning directions and the operational development models underpinning change management in schools (OECD, 1999). Therefore the case studies were written up to facilitate classification of the data into categories (Perry, Riege & Brown, 1998, p. 1956; Strauss & Corbin, 1998, p.114) across the different studies. The case reports are issue-oriented, and therefore it was appropriate for the common approach to reflect all four research questions, which also facilitated triangulation with the data from the other methods.

3.1.3 Methodology for the investigation of professional development (RQ3)

Teacher professional development has many dimensions and takes many forms (Tuviera-Lecaroz, 2001, p. 1). The dimensions include quality, quantity, setting, delivery, responsibility and application. The forms include formal and informal, individual development, etc. The critical dimensions of ICT training for differing types of teacher include the emotional aspects and transfer of learned skills to classroom contexts (McKenzie, 1998). Other aspects requiring attention include the way in which planning of professional development is conducted; this can be improved through staff surveys and other assessments (McKenzie, 1998). There is the question of whether pedagogy or technology is the main driver for professional development in the area of ICT for school education. This is particularly important when the delivery is conducted using open or distance learning techniques (UNESCO, 2002). Providing a repertoire of good practice is not in itself a sufficient condition to ensure teachers adopt new pedagogies congruent with the innovation of ICT (Bottino, 2003, p. 5). Therefore the approach taken to collect, evaluate and analyse data about teacher ICT professional development was an eclectic one. Following the techniques used by Moonen and Voogt (1998) data were gathered from structured interviews with teachers in the case study schools and experts involved in related national projects, and from local policy documents in the schools.

3.1.4 Methodology for the investigation of stages of development (RQ4)

Research Question four was designed to analyse the underlying models used in policy making and illuminate forecasts of ICT development in school education. An important part of policy analysis and formulation consists of predicting the effect of possible policy instruments. Included in this process is an evaluation of the consequences of inaction; the effects of a failure to make policy are examined as seriously as possible new policies. The consequences of an innovation are critical to our understanding of policy development. “Policies are built on theories about the world, models of cause and effect” (Bridgman & Davis, 1998, p. 5). Forecasting is a discipline that has its own cast of critics and supporters. It has been argued that all forecasting falls into one of two domains - a view that the future consists of “continuous progressive evolution”, and alternatively, that the future will be determined by “discontinuous change” (Jones, 1980, p. 23). Supporters of developmental futures tend in the main to be optimists and the latter group are inevitably labelled as pessimists. A variety of forecasting techniques are available and include Delphic studies, axial principles, megatrends analysis and modelling. Each of these has some attributes that have made them useful for education policy analysis, and were used to guide the methodology.

The Delphic technique (Hogwood & Gunn, 1984, p.136) was used at the RAND organisation in the 1950s (Gordon & Helmer, 1966). It relies upon the “MacGregor Effect” reported by Loye (1978) which showed that predictions made by a group of people are more likely to be right than predictions made by the same individuals working alone. The technique is particularly useful when the field of interest is so new as to have inadequate historical data for other methods to be applied (Lang, n.d.). The accuracy of the technique for short-range forecasting was established fairly conclusively (Ono & Wedemeyer, 1994), and its validity for long-range forecasting was shown in a 1976 study evaluated much later (Ascher & Overholt, 1983). Difficulties with the Delphi technique centre on the selection of participants, the tendency of individuals to follow group norms (Dalkey, 1972), and coordinators who structure the feedback or frame questions that bias the results (Masini, 1993). A group of 13 is considered optimal (Dalkey, Rourke, Lewis & Snyder, 1972; Debecq, Van de Ven & Gustafson, 1975; Ziglio, 1996, p. 14). A modified Delphi technique was therefore deemed appropriate for this study, with seven experts selected from the different countries examined. “Be cautiously sceptical of experts … always use more than one” (Pal, 1992, p. 278). They were all asked the same questions, but not provided amalgamated feedback for a second round of responses. This modified Delphi technique was used as a starting point for the development of a model using grounded theory in the synthesis stage of Research Question four.

The aggregation of terms required by grounded theory for model building was influenced by axial principles and megatrends analysis. These can be categorised as part of the “continuous progressive evolution” domain of forecasting. Bell (1973) used axial principles to describe the development of post-industrial society. Allen (1996) concurred with Bell’s description of the transition driven by production and profit from pre-industrial to industrial society; while knowledge and information are driving the transition to post-industrial society. Given that equity is a matter of significant concern to educational administrators and practising teachers, the application of Bell’s axial principles appears to be a sound and valid approach to employ when considering RQ4. In order to apply this methodology, it was necessary to identify the appropriate axial principles that would determine the adoption of ICT in education.

The megatrends approach is similar to Bell’s axial principles (Naisbitt, 1982; Naisbitt & Aburdene, 1990). The two relevant megatrends are #2 (1982) ‘Forced Technology → High Tech/High Touch’ and #1 (1990) ‘The Booming Global Economy of the 1990s’ which combine to provide the paradox of the highly inter-connected economics of the world and the rise of individualism. Each successive economic revolution (from agrarian to industrial, and industrial to post-industrial) has resulted in a greater degree of independence of the individual. Yet also, at an economic level, each increase in individualism has been built upon trading links that have stretched further afield. An example of this kind of individual empowerment can be found amongst the North Carolina “ruthlessly small” nanocorps, which operate successful one-person businesses world-wide using the Internet (Salmons & Babitsky, 2000). Technology has made large industrial processes more able to accommodate the needs of single customers into the mechanisms that generate economies of scale (Dawson, 2000, 4.47; Robinson, 2002). The analogous concepts for ICT in school education are the idea of differentiation (catering for the learning needs of the individual) and digital replication (whereby learning materials can be disseminated globally without loss of quality). These concepts had to be factored into the construction of a consolidated framework of ICT development.

The last of the four predictive forecasting techniques to be considered was mathematical modelling This technique has been used to predict limits to the growth of human societies (Meadows, Meadows, Randers & Behrens, 1972) with a sustainable limit at 20 billion, though most others estimate a peak of about 8.9 billion by 2050 (United Nations, 2000, p. I2). Given this predicted population growth, and the concern for equity and technological determinism expressed in the introduction to this thesis, the question arises as to the linkage between a technology and its social implications. “The shaping of a technology is also the shaping of a society, a set of social and economic relations” (Bijker & Law, 1992, p. 105). An important determinant of the consequences of a technology upon society is the way its introduction is managed through corporate governance, copyright or patent legislation. This was evidenced by the case of the world’s most used micro-computer operating system software. Nineteen of the State governments in the USA won a case charging the maker, Microsoft, of monopolistic practices (US District Court of Columbia, 2000). Another determinant of interest to ICT in school education was the penetration of the innovation into student homes, and therefore web-data mining was used to gather data about future access trends and the likelihood of universal home access.

The development of a generic framework for ICT in school education was therefore shaped by the views of the experts through a modified Delphi technique. It took account of axial principles and megatrends illuminated by the case studies and the literature, and reflected the rapidly growing capacities of the underlying ICT.

3.2 Background to the research approach

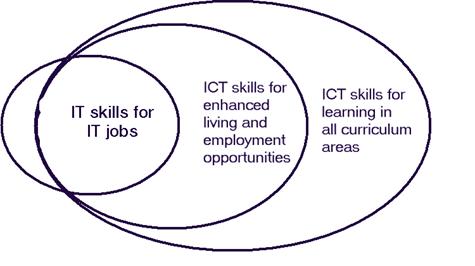

The literature review provided background on policy making, implementation and practice and professional development in respect of ICT in education. It was important for the research approach to facilitate cross-national insights into each of these areas, because this provided the variety of contexts necessary to give confidence in the conclusions (King, Keohane & Verba, 1994, p. 30). The design process required a series of progressive steps to collect and code data relevant to the research questions to make categories. Using a grounded theory approach, the categories and their properties were then integrated through selective coding (Corbin & Strauss, 1990, p. 14). The initial step took into account the reasons why computers are included in the school curriculum, ranging from a pragmatic and economic rationale to a broader view related to improving the quality of learning in all subject areas. This generated a conceptual understanding of the relationships between the various types of ICT in school education (see Figure 4).

Figure 4: Initial model for understanding ICT in the school curriculum

Figure 4 shows an initial relationship between the different kinds of ICT use in learning. It shows that ICT skills for IT jobs derived from the economic rationale are a partial sub-set of those needed for enhanced living and employment opportunities (derived from the social rationale). The skills linked to the pedagogical rationale were seen as a partial super-set of all of these. Questions arising from this initial visualisation were related to the nature of content and process skills of the ‘IT skills for IT jobs’ which were not embraced by the enclosing sets, and the nature of the distinction between economic and social rationales. Also, this visualisation was constructed upon the assumption that all student use of ICT could be categorised together, whereas the literature review had distinguished clearly between the relative opportunities students had to use ICT at home and school (Meredyth et al., 1999; Australian Bureau of Statistics 2000c, 2000d).

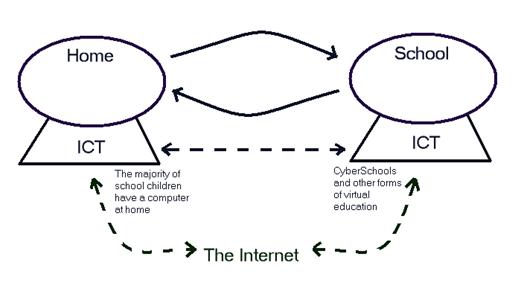

As the research progressed it became clear that this school-centric view was insufficient to encompass relevant factors stemming from social and vocational rationales. Economic imperatives for each country emphasised the ‘IT skills for IT jobs’ aspect of the curriculum, yet an increasing number of computers in students’ homes tended to emphasise the use of ICT for learning generally. Therefore, a broader picture of the way in which classroom computer use was situated with respect to external influences was conceived (Figure 5).

Figure 5: Initial understanding of relationships between home and school computer environments

In this figure, solid arrows represent the personal relationships between home and school. This distinguishes them as direct relationships, in contrast to the electronically mediated or “virtual” relationships that are also possible (shown as dashed lines). The figure shows how ICT can be an adjunct or element of school and home life, and also a conduit between these two locales. This communication can be direct or it can be mediated through the Internet, which itself offers additional learning and communication capacities. These initial integrations of the data were only used as a first step in the development of a new understanding.

3.3 Research approach

A multi-method grounded theory research design that used a comparative case-study approach with semi-structured interviews, content text analysis and case studies would allow the conclusions to be strengthened through triangulation (Webb, Campbell, Schwartz & Sechrest, 1966). A summary of the approach is shown in Table 6.

|

Date |

Project stage |

Data Collection & Analysis |

|

March 1999 – January 2000 |

Problem definition and literature review |

Build document database |

|

September 1999 |

Sample selection |

Construction and trial of structured interview formats |

|

October 1999 |

Approach prospective expert panel members and case study schools |

Web-data mining to gather background information on case study schools. Questions sent to proposed interviewees. |

|

November-December 1999 |

Field studies in USA, England and Estonia (a)

|

In-depth interviews with expert panel members Data gathering for school case studies: interviews with ICT coordinators, teachers and students, classroom observations, collection of local policy documents, teaching materials and school web-site or systemic accountability data |

|

December 1999 – March 2000 |

Selection of national level policy documents from web-mining and as guided by expert panel |

Transcription of interviews with expert panel members and case study school teachers Participant review Writing case studies Content & issue analysis Writing up of thesis |

|

January 2001-August 2002 |

Writing of journal article, national conference organisation and work commitments |

See Fluck, 2001b; http://www.pa.ash.org.au/acec2002/default.asp |

|

September 2001 |

Field study (b) in Estonia |

Obtain new national level policy documents |

|

September 2002 |

Field studies in Australia |

Data gathering for school case studies (as before) Writing of additional case studies |

|

October 2002-May 2003 |

Analysis and reporting |

Open coding of interviews and policy documents; category formation, property allocation and dimensioning Category grouping and logic diagram construction Writing up of thesis |

Tools were required to gather data relevant to each Research Question. Although each question covered a different area, there were many overlaps among them (such as the linkage between policy and professional development which is often subject to policy guidelines). These overlaps were also encountered when data sources were selected and they illuminated more than one research question. First-order (raw) data (Eliasov & Frank, 2000) was collected from decision-makers at the national policy level and additional information was collected from public and private sources to provide contextual data for each participant. These additional sources included web data-mining (Hearst, 1997) and published literature to provide alternative perspectives. Each of these grounded the data in the field, adding to the soundness of the findings.

3.4 University ethics approval

Permission for the project was sought from the University Ethics Committee. The proposal contained full details of the research approach, a description of the project and the framework for the semi-structured interviews. The study was approved, with the condition that an Information Sheet be produced for participants in the study. This was done and is included in Appendix 6.5.

3.5 Sample selection

There were three separate samples: first, of countries for inclusion in the study; second, of individuals for the expert panel and third, of schools for the case studies.

3.5.1 The sample countries

The countries sampled for investigation needed to have significant levels of ICT use in schools, otherwise there would be nothing to include in the case studies. However, to make the study generalisable, they also needed to have as rich and broad a range of cultural values and other factors as possible within the limitations of travel budget, time available and researcher linguistic ability. This sample is therefore a purposeful sample, chosen for the maximum opportunity to learn about the phenomenon (Merriam, Mott & Lee, 1996, p. 9).

The USA was selected because of its globally dominant position in trade and politics, together with its reputation for advanced uses of computers in education. The link between the researcher’s professional association in Australia and ISTE in the USA was also an enabling factor.

England was selected because of the parallels between it and the USA in respect of ICT in schools. The commonality of language between the two countries and the researcher’s own made these easily approachable sources of data, especially valid for comparison with Australia. Their similar characteristics in terms of GDP per capita, student:teacher ratios and students/computer made them valid comparators for the Australian situation.

The validity of the study would have been restricted if data were only collected from wealthy highly industrialised countries. Estonia was chosen as a suitable contrast to these other countries. It had a very low GDP per capita and a very small population with national income principally deriving from forestry resources. However, it offered an environment accessible to the researcher, since English was widely understood and it had a reputation for advanced take-up of computers in the post-Soviet era. The existence of the Tiger Leap Foundation as a national organisation to promote ICT in schools gave a point of contact similar to that found in the UK and USA. The number of Internet hosts per head of population was above average for its GDP (Dodge, 1998) putting it on a similar level to the UK in this respect (UNDP, 2000).

3.5.2 The sample of expert panel members

Communication is an essential characteristic for the diffusion of innovative ideas (Valente, 1995; Karsten & Gales, 1996). Strogatz and Watts (1998) argued that ideas spread through personal contact (bottom-up) as much as through media (top-down) in their investigations of small world theory. This theory emerged from a study of communication networks and allows the conclusion to be drawn that human networks have a connectivity somewhere between that of regular and purely random networks (Monge & Contractor, 2002). An average of 3.65 links was found between the 225,000 socially connected actors around the world (Matthews, 1999; Watts, 1999). The social network of educators involved with ICT can be considered in the same way, especially since they were highly likely to be laterally connected through Internet access in the post-modern networked organisational form that has evolved through modern communications technologies from top-down hierarchies such as bureaucratic and multidivisional forms. Members of the expert panel were therefore approached to form an opportunity sample following identification in the first and at least one other of the following categories (which are also used in the following Table as selection criteria codes):

1) The individual was involved through an executive role in educational ICT projects at a national level, and

2) Was a senior member of an organisation with a prime responsibility for ICT in school education; or

3) Was recommended by at least one other member of the expert panel as having a significant role; or

4) Was appointed as the spokesperson by a national organisation which had a prime responsibility for ICT in school education.

The membership of the expert panel is described in Table 7, representing a mix of national decision-makers and people engaged in projects of national significance.

|

Country |

Expert panel member |

Position |

Responsibilities |

|

USA |

DM |

Vice-president of International Society for Technology Education (ISTE) [1 & 4] |

Nominated by ISTE: manager of national project on teacher and student ICT standards |

|

Estonia |

EM |

Director of nationally funded ‘Tiger Leap’ computer education project for Ministry of Education [1 & 2] |

To provide targeted co-funding for school ICT equipment and direct a program of professional development for teachers |

|

Estonia |

TE |

National project officer |

Direct externally funded project to develop administration information systems for schools |

|

England |

NM |

Schools Director of Becta [1 & 2] |

Direct research and development into ICT in schools |

|

England |

KB |

Officer of Teacher Training Agency |

Implementation of national program for teacher professional development in ICT |

|

England |

MR |

Independent consultant [1 & 3] |

Quality assurance of national program for teacher professional development in ICT |

|

England |

BM |

Professor of Education in University largely using distance delivery of education [1 & 3] |

Major supplier of professional development for national program of teacher professional development in ICT |

3.5.3 Selection of schools for case studies

In each of the sample countries one primary and one secondary school from the public sector with mixed gender students were selected for the case studies. The schools selected for case studies were chosen because:

· They were accessible from the locations designated by the members of the expert panel for their interviews.

· There was sufficient information available on the world-wide-web about each school to assure the researcher that ICT was being used across the curriculum.

· They were not selected on the basis of exemplary performance in respect of ICT (except in Estonia where selection was guided by the national ‘Tiger Leap’ team).

The case study schools therefore represented an opportunity quota sample. In one case (a primary school in England) the school selected was not visited because of illness of the responsible teacher on the agreed meeting date.

3.6 Data gathering

Data were gathered from three sources (policy documents, expert panel and school case studies) using two main tools. These were the face-to-face interview and web-data mining. This section describes the protocols used in conjunction with these two tools. Concerns about the unjustified use of multiple methods have been raised:

Two poorly designed and sloppily conducted evaluation strategies will yield no better picture of the findings than one poor study. Mark and Shotland (1987) maintain that multiple methods are only appropriate when they are chosen for a particular purpose, such as investigating a particularly complex program that cannot be adequately assessed with a single method. (Reeves, 1999)

In this study multiple methods were intentionally chosen to maximise the trustworthiness of the data. The establishment of a framework in Research Question four from which future directions for ICT in schools could be derived was a complex task for which multiple methods were appropriate. Documentation would provide data about existing practice, but future directions would be more easily identified through interviews with the national-level decision-makers to determine the pathway they perceived policy was on. These data were then combined with those from the case studies using selective coding and model building.

Following piloting, the structured interview formats were changed to make the questions to each of the three categories of respondent sufficiently distinct, but with overlaps in respect to policy and home use of ICT. When the questions were sent to interviewees as part of the meeting arrangement process, queries about local interpretation were answered by e-mail. This gave a commonality of approach and helped to make the interview a more productive event. The interview technique enabled narrative inquiry where the contributors to the study built a story of the situation as they saw it from a personal perspective. In this sense, the perspective gained was a privileged one, since most of the participants had highly instrumental roles in the determination of public policy for computers in schools. The partisan nature of this perspective and possible participant halo effect was moderated by the school case studies and policy document content analyses (Cohen, Manion & Morrison, 2000, p. 157).

Through their responses to the structured interview questions the interviewees told the national history of ICT in education, revealed some of the hopes and fears of the policy framers as they perceived them, and described their expectations for future directions. The researcher had to strike a balance between encouraging trust which would enhance disclosure, and over-emphasising the importance of any particular statement which would bias responses. He was a foreigner and therefore this mitigated against hiding otherwise unpalatable aspects of the decision-making process because the interviewees were not having to justify their actions to the group of people that had been affected. This encouraged interviewees to be as revealing as possible.

3.6.1 Interview procedure

Face-to-face interviews were selected over telephone calls or written surveys because of the small number and preference of participants, their key nature in determining policy in their countries, and the possibility of improved openness in face-to-face interviews (Gillham, 2000, p. 62). The selected individuals were contacted by e-mail to request their permission to participate. When an appointment had been agreed, the individuals were sent by e-mail a short introduction to the study, its main aims and research questions, together with a set of questions to be addressed during the interview (see Appendix 6.4), at least three weeks before the appointment (except in one case where a national expert was recommended for inclusion during the country visit). A request to consider permitting audio tape-recording was included in this exchange of e-mails. Most interviewees found the questions a useful guide to the general area being investigated. In most cases participants asked for a further verbal explanation about the questions as a preliminary to answering.

The interviews were conducted on a private one-on-one basis at their workplace[1], helping them to be at ease to overcome apprehension and thus increase openness. At the commencement of the interview each respondent was asked if they consented to audio-tape recording of the conversation, and this was done only with approval. While the interviews were conducted using the structured interview schedule, other issues originating from the interviewees were followed using probes (Gillham, 2000, p. 69) such as “please explain that to me” or “how does that link to…?” The importance here was to maintain a balance between consistency and discovery (Strauss & Corbin, 1990, p.182). At the conclusion of the interview, the respondents were given an opportunity to request a transcript for review. Only one such request was made and the transcript was emailed back to the respondent within a month. It resulted in no changes to the transcript. As soon as possible after each interview, the recordings were transcribed, reviewed and edited using Dragon NaturallySpeaking voice recognition software (Zick & Olsen, 2001), which was reasonably fast and accurate.

3.6.2 Gathering information using data-mining from the world wide web

The collection of policy documents and case-study information formed two parallel activities in this research study. Policy documents were gathered from the initiation of the project in 1998, and this collection was added to throughout the study to December 2002. Case study information for each country was gathered from the world wide web prior to visits in November/December 1999, and from the interviewees at that time. In many cases these informants referred the researcher to materials that were accessed through the Internet or by post after returning to home base. Many of the materials were available in electronic form. They were stored locally in conjunction with the reference list for the thesis in web-format to form a database that could be searched by keyword or author.

3.7 Reliability and validity

The general question of validity of the data requires the researcher to examine other possible explanations for the observed phenomena than the broad aims being investigated. A variety of methods could be used to determine the authenticity of research findings, but a general helpful distinction is drawn between issues of internal and external validity. The issue of validity of the data was considered against the criteria established by Campbell and Stanley (1963) and revised in Campbell (1969). Since the study was not essentially experimental, the history effect was not strictly applicable since there was no pre- and post-test to determine the effect of a treatment. However, in a wider sense there was a need to separate out the behaviours which related to ICT in education and those which were the result of other factors such as new curriculum frameworks, changes of government, etc. The threat was addressed by the researcher becoming contextually sensitive, demonstrated by including a short description of each country investigated in the Appendix, and by giving relevant background information for each school case study.

The problem with regression artefacts was considered. This threat occurs when individuals in a study have been selected upon the basis of extreme positions. In some ways it could be argued that all the participants in the case studies were fundamentally in favour of computers, since each had a position of responsibility at some level to manage, introduce or encourage the use of computers in schools. In this sense they were a biased group. However, the study was aimed at tracking and describing the growth of ICT in schools, and to this end it was important to contact people who were involved in the process rather than detractors or those who were uninvolved, since they could probably contribute little knowledge to the study. Many of those interviewed (particularly MR) espoused a highly critical view of some uses of ICT in schools. Such a critical view was in alignment with his quality assurance role for the national training scheme. In each country except the USA more than one expert was interviewed, and this provided an opportunity to verify statements, reducing the threat of bias amongst respondents. The possibility of collusion remained, but the choice of experts from different countries and sometimes competing organisations helped to moderate the risk. The threat to the validity of the study was acknowledged and considered in the analysis stage of the work.

The selection threat was a potential threat to internal validity, since the various countries would be compared in the analysis. However, there were a limited number of people in each country who had carriage of the ICT agenda in schools, and it was from this group that selections were made. The bias occurring from the actual selection was to some extent mitigated by the literature search to ensure interviewee data were related to published material. Experimental mortality was only a threat in Estonia where academics in the University of Tartu who had historically been involved in setting up the national ICT program were unavailable for interview. This was not a significant problem since the actual respondents had largely taken over and were driving the process along new paths that extended planning from previous years.

The selection-maturation interaction effect on the data was of particular interest to the study since differential rates of autonomous change between countries were being mapped and followed. The choice of countries for study was important to address this aspect of validity because they included culturally diverse and developmentally overlapping sources of data.

External validity was also considered in the light of Campbell’s (1969) list of potential threats. If the analyses of the policy documentation, interviews with experts and school case studies were to be applied to the Australian situation, it was necessary to examine any potential source of bias that might make the findings inapplicable. The constraint on transferability lay in the differences in governmental structures and the various priorities for schooling within each Australian state. The interaction effects of testing were considered unlikely to be a problem in that the chances of any particular respondent communicating with any other about the research program were considered small. Although it was possible that respondents could interact with national level decision-makers in Australia and that some of this (especially in the case of professorial exchange visits or international conferences) could be influential, was not a threat that could be eliminated. It was however mitigated by the relatively small number of experts interviewed.

The interaction of the selection and experimental treatment was not a consideration as no treatment was given in respect of the school case studies, and this applied to multiple-treatment interference. The general class of ‘Hawthorne effects’ as a reactive effect was not considered significant, since the whole area of investigation was one of dynamic change and perpetual evaluation which simultaneously made this unavoidable and backgrounded the risk. The experts on the panel were in a good position to make strategic decisions and may have tended to be positive about their own country. However, because of their significant roles, they were also aware of any shortcomings of policy or implementation, and this aspect was probed to provide balance and neutrality to the data. The case-study schools were susceptible to this threat, so it was minimised by approaching the school directly through the principal and organising visits which would disrupt teaching activities minimally.

The threat to validity posed by Campbell’s (1969) irrelevant responsiveness of measures was considered seriously since apparent findings emerging from irrelevant components would compromise the findings. The process chosen to reduce the significance of this possible threat was to triangulate the data sources (policy document analysis, interviews with experts and school case studies). Common results between two or more of the sources would be less susceptible to this threat.

The irrelevant responsiveness of measures was a threat to be considered seriously since apparent findings emerging from irrelevant components would invalidate the findings of the study. The process chosen to reduce the significance of this possible unreliability was to ‘triangulate’ (Campbell & Fiske, 1959; Cohen, Manion & Morrison, 2000, p. 112) the data sources (literature, interviews and observations) and draw conclusions for each case study country where these aligned. This could not be guaranteed to eliminate all such sources of error, but the process could be used to give an estimate of the probable validity of each finding.

Finally, the irrelevant replicability of treatments alerted the researcher to the possibility of findings that were not due to the components of the complex situation under study. For instance, any generalised model of stages of development that might be discovered could be distorted by a sudden change of government to one that decided to eliminate ICT from primary schools. Alternatively, the study might concentrate on identifying the characteristics of phase transitions between stages of development, when the underlying mechanisms relied upon fewer or more stages. This was not an easy threat to meet except by emphasising the ecological validity of the study (Johnson & Christiansen, 2000, chap. 7). Data collection was enhanced by conducting the research in natural settings, which required attention to the description of explanatory variables as well as the setting (Open University, 1979, p.40).

Since a multi-method methodology was selected, the general question of validity needed to be dealt with in different ways for each type of data source. In the case of policy documentation describing curriculum or training initiatives, these were collected by the researcher from individuals involved in their development.

In the case of materials available from the world-wide-web, these were generally downloaded and stored locally to permit the investigation of meta-tags and other authentication markers. Although this does not of itself guarantee the provenance of a file, a local copy did permit re-visiting of the version that was available on the day of download. Access to these materials is not provided on the CD-ROM version accompanying this thesis because of copyright restrictions. However, the references section states the full uniform resource locator which can be used to locate the web-site of the source institution.

In the case of personal interviews, the interviewer transcribed these as soon after the event as practicable. Great care was taken to make these as accurate as possible, with the interviewer’s own comments being as faithfully transcribed as those of interviewees. A full transcript of each interview has been made available on the CD-ROM version accompanying this thesis, for purposes of verifying the analysis.

3.8 Data analysis

The data were analysed using the principles of grounded theory research according to research question and source. The procedure of data collection was accompanied by the process of descriptive coding to organise situations, personal perspectives and literature in ways that were meaningful. This process was followed by typological analysis (LeCompte & Preissle, 1993, p. 257) which aggregated similar categories.

Data from the sample countries were selected and investigated at three levels. The first level was that of national policy, undertaken through text analysis and comparison and synthesis of interviews with national-level policy-makers. The second level was that of schools, where once again extant documentation was examined and the ICT coordinator interviewed. The third level was that of the classroom, where the researcher visited teachers working with computers in a range of educational disciplines, to see to what extent national and school policy had penetrated into classroom practice. Data from the school and classroom levels were synthesised into school case studies, structured in a standard form related to the research questions. The school case studies were analysed using the process of constant comparison, which allowed data from several different sources to be integrated.

As data were gathered from a variety of sites, content analysis was used to identify significant categories and commonalities (Gillham, 2000, pp. 71-75). Interviews were analysed using issue analysis through grounded theory (Lincoln & Guba, 1985, p. 205) because of the small number of experts, the time available and the focus on issues. This evolved into a developing framework to assess ICT integration in Australian states, and to make a judgement about development pathways. The use of an evolving framework employed an iterative process of re-examination of emerging categories during data analysis, maximising the opportunity to accept new knowledge (Pandit, 1996).

3.9 Limitations

All research embeds decisions about the balance between available resources and the effectiveness of techniques. It was important therefore to recognise potential sources of bias and error in the conduct of this study. Researcher bias emanating from personal reasons for wanting to conduct the study was a consideration. This was regarded as an acceptable limitation since the motivation component was a necessary condition for the study to be completed. There were further possibilities for error due to terminological inexactitudes and other human communication problems. Efforts to eliminate these sources of error were considerable. The discussion in a previous chapter attempts to precisely identify the meaning of the vocabulary used in each country, as one way of translating comments into a standard meaning. In addition, when in Estonia, the researcher took every opportunity to match what was said at interview with materials translated into English by an independent person.

While interviews were conducted in a friendly vein, the researcher attempted to remain non-judgemental and to interact with what the interviewee said. This strategy was used to assure respondents their opinions were appreciated and to increase their openness. It cannot be known to what degree their disclosure was influenced by this strategy, or whether significant bias in the nature of their opinions resulted.

A limitation in such a study can be the difficulty of respondents being under pressure to overstate the positive side of their story, and therefore be biased in their responses (Yin, 1994). Conducting these interviews privately in the workplace of the subjects minimised these pressures, since they were not on public display and the researcher made it clear that the intention was to publish findings based upon results gathered from a mixture of settings and countries. The process of exchanging e-mail before the interview helped to establish a degree of trust. This trust was built into rapport by responding equally to positive and negative examples of ICT in the interview. This meant the interviewer was open to alternative interpretations of the development pathway expressed in the proposed model. In addition, much of the data was gathered from multiple sources, such as several experts in each country, case study information from documents and interviewees and so on. The audio-tape recording of interviews enabled a more objective analysis to be conducted after the event. These multiple perspectives facilitated the verification of data (Merriam, 1998).

Another limitation of this study relates to the small number of countries included in the case studies. While a certain diversity of cultural background was incorporated into the design, the majority were English-speaking and Anglo-Saxon. A greater range of validity might be claimed if a greater diversity of cultural backgrounds had been included, such as more African, South American and Russian examples. Data from such geographically dispersed and culturally different situations could have led to greater generalisability of the study. In mitigation of this limitation, the increasingly competitive environment of globalisation (Peng, 2002, p. 18) was tending to make economies converge, providing a reasonable degree of generalisability to the findings.

3.10 Chapter summary

This chapter has provided a description of the study methodology, and the substantiating rationale for its adoption. Policy documents were selected with the guidance of the expert panel members and their contents analysed comparatively. Practice was investigated through case studies using multiple perspectives, while teacher professional development was studied using a variety of sources, including school-level policy documents. Stages of development were considered through interviews with the expert panel members which were extensively coded to form categories using a grounded theory approach. The emerging theoretical framework was critiqued, as well as the protocol for conducting interviews and gathering other data. The issues of validity and reliability were discussed.

The following chapter describes the findings from the policy document comparisons, what the experts said and the school case studies.

[1] Except in one instance where a quiet pub was selected by an expert panel member as convenient for the travel arrangements of both parties. The session was made silent for one minute in recollection of Armistice Day.