Integration or

Transformation?

Integration or

Transformation?

A cross-national study of information and communication technology in school education

Appendix 6.2

School observation case studies

This part of the Appendix contains case studies derived from school visits in each of the four main countries visited. The schools visited were:

United States of America:

Case Study 1: Theodore Roosevelt Middle School

Case Study 2: South Eugene High School

Estonia

Case Study 3: Lyceum Descartes

Case Study 4: Pärnu Nüdupargi Gùmnaasium

England

Case Study 5: Tadcaster Grammar School

Australia

Case Study 6: Applecross Senior High School

Case Study 7: Winthrop Primary School

Each of the case studies is organised in the same way, with these main sections:

Background information: giving the basic demographic statistics and recent history of the school situation.

Policy formation: noting the relationship between internally developed policy and those imposed from outside the school.

Implementation and practice: operational details and vignettes of classes observed.

Professional development: ways in which teachers are trained to use and deploy ICT as a learning resource.

Stage of development: an assessment of the relative stage of ICT use in teaching and learning.

Issues arising: summary of the major findings from this case study.

6.2.1 Case Study 1: Theodore Roosevelt Middle School

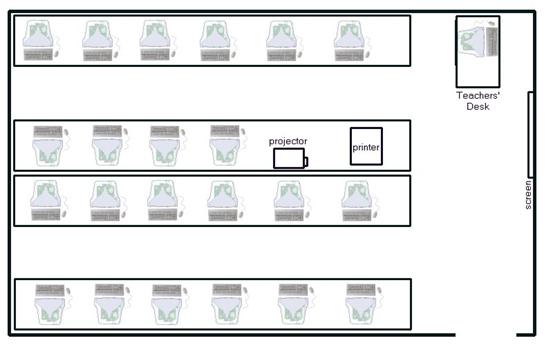

Figure 8: Theodore Roosevelt Middle School

6.2.1.1 Background information

|

Age Range |

11-14 |

|

Students with home computers |

90-95% |

|

Enrolment |

770 (mixed gender) |

|

Student:computer ratio |

6.16 : 1 |

Theodore Roosevelt Middle School lies in the city of Eugene in the state of Oregon on the western coast of the USA, north of California at about 45° of latitude. Eugene is a city of approximately 130,000, with another 130,000 in the surrounding Lane County. Eugene is Oregon's second largest city, covering approximately 36 square miles, with the Willamette River running through the heart of the city. Governed using the council/manager model, the city runs a regular series of plebiscites, which have legally binding results. City council meetings are televised on the cable network, with teen council meetings treated the same way to facilitate understanding and involvement in decision-making across the population. A significant proportion of the school students (17.5 percent) was enrolled in the French immersion program at the school. 13.3 percent of students were eligible for free or reduced fee school lunches, indicating a relatively prosperous catchment area.

One of the educational destinations for school leavers was Lane Community College. This college had its main buildings in the centre of town, where it ran a large number of face to face programs as well as in suburban centres. Some courses ran as tele-courses on-line. The clerical staff of the college informed the researcher that these were very popular, generating as many enquiries as the face to face courses.

On the day of the observation visit, the school was engrossed in an examination of the way in which students selected option course subjects. While other schools used a computer-based system, Roosevelt continued with the day-long drop-card arena registration method. The process involved each student considering a list of electives, and meeting with the course teachers to ask for a place in each class they have selected. After a period when students place their choices, any over the size limits of the class are “bumped” and these students had to select an alternative. The process proceeded until everyone had a full quota of classes. Various bodies within the school seemed to be vocal in their support or criticism of the system (Enos, 1999, p. 7).

6.2.1.2 Policy formation

State educational standards were maintained through a series of state-wide tests for students in grades 3, 5, 8 and 10 (for the Certificate of Initial Mastery). These were computer-marked multiple-choice tests combined with performance assessment essays. Performance on the tests was considered important, and the school district published aggregated student learning outcomes in the context of comparative figures from other districts and states on its website (http://www.4j.lane.edu/).

Figure 9: SS, computer coordinator at Roosevelt Middle School

SS was the computer coordinator for the school. He had become a teacher after working in the computing industry and had worked in the school for 15 years. SS taught mathematics, “the computer projects class and 6th grade explore [sic] … SS likes Roosevelt because of the freedom teachers have to teach what they want and to teach it the way that they want” (Schwarz, 1999). He considered the facilities in the school to be extremely good, including very high-speed connections to the Internet (such that the author was able to access his web site in Tasmania with greater speed than if he had been sitting at his office workstation). The quality of the IT infrastructure in the school was having a distinct effect upon the kind of skills the students were learning. Even the introductory course included some key skills for accessing the Internet, and some creative elements requiring powerful machines and high-quality software.

SS: All 6th Graders take a 6 week introductory class where they learn how to use the computers at Roosevelt, how to navigate the network, they learn keyboarding skills. They do some multi-media authoring and they do some e-mail. Basic things like that. Beyond that there are electives that include web-design, a little bit of programming, more multi-media design – that’s available for 6th, 7th and 8th Graders. (SS2)

The organisation and management of this IT infrastructure was mainly under the control of SS, with additional technical support. However, the responsibility for determining policy direction was managed by the school through a school policy committee. This ensured the involvement of a wide range of teachers, and the representation of a mixture of skill levels and curriculum areas. He commented that “We have a technology committee, which meets twice a month. And basically we set the technology policy and standards for the building” (SS6). There was some discussion about the benefit of national standards, especially those which had been developed nearby. SS was aware of teacher burn-out and dissatisfaction with the continuing stream of new policies in almost every area. He discussed the pendulum swing between competency- and norm-based outcomes:

Another teacher made the comment that teachers are distancing themselves from standards development, since competency based outcomes had been used previously, and had been dropped, so there was little desire to repeat a similar fruitless exercise. (SS10)

SS estimated that between 90 percent and 95 percent of students had a computer at home. However, his reading of the situation was that staff knew of some students who did not have this kind of facility, and, even though the vast majority of students were also able to access the Internet, teachers would not require Internet access for work to be done outside school. This issue of equity was not tested by the school in a factual way, but remained a strong impediment to developments in this area because of teacher expectations and attitudes.

AF: Question 8: Do your policies cover the relationship between home and school computing?

SS: Teachers would not expect students to get information from the Internet at home, but they know many students would provide it. [For] Anything that requires students to use computers, they would provide time in the computer lab. (SS19-20)

Although the school was not responding to externally imposed ICT policy, it was likely that the testing regime would determine much of the learning activity in the classroom.

6.2.1.3 Implementation and practice

NN was taking a Mathematics class of 19 girls and nine boys 12-14 years old where they were studying pre-algebra. NN said they would normally use the computer for research and independent learning during the course of a week. In this lesson the students were directed to the web site <www.jenine.org>, and asked to work through the geometry-based who-dun-it problem solving exercise there called ‘GeoGirls: The Perfect Crime’. This was demonstrated by the teacher using an LCD tablet over an OHP. They had to work out from the story and clues which thief had stolen the Rhombus Gem.

They were challenged to design over a 4-week period a similar exercise based upon algebra and pre-algebra. The design work would be shared by all, and a pair of expert students would implement the web-site that resulted. When asked their opinions of these computer-based learning activities, the students expressed great enthusiasm (“cool!”). Some said they undertake learning activities related to classwork using computers at home. For example, one student said he had made a slideshow comparing television programs for a project using PowerPoint. Quite often he used the Internet to research assignments, and then word-processed them.

Figure 10: Logo from mathematical mysteries web-site.

|

|

|

http://www.efn.org/~kinne/geogirls/questions/story.html = http://www.jenine.org/geogirls/index.html |

Teacher DM2 was observed teaching two lessons. The first was to 25 twelve-fourteen year old students undertaking learning activities in astronomy. The web-site being accessed was at data.4j.lane.edu:59/WebSearch2000/contest-list.html where a competition was in progress. The students had been allowed to access an astronomical telescope at Pine Mountain which permitted remote operation over the world wide web after they had participated in a web-based training exercise. This activity was entered by DM2 into a competition for teachers, and had won her the prize of eight computers used in the second lesson (SS9). The second class included 28 twelve-fourteen year old students. Under the topic of searching for extra-terrestrials, they studied Science and in particular, Chemistry. This was done by looking at the science behind attempts to seek out extra-terrestrial life, such as the spectra of chlorophyll, the interpretation of satellite images (What does a typical vulcanised region look like to a satellite?) and so on. The class was undertaking a circuit of nine activities as follows:

· Seeing in a new light (spectroscopy)

· What’s a Fossil? (making your own fossil)

· Canned Heat (black body radiation)

· Photosynthesis/Elodea (oxygen production by an organism in a test tube)

· A solvent for life (water analysis)

· Micro-world/Micro-fossil (microscope use)

· It’s Alive (satellite data analysis - applying what we know about satellite photographs to pictures of Pluto)

· Space Oasis (read on-screen and summarise)

· Stormy Mars (water cycle/earth timeline - read articles and do comprehension worksheet)

Three of these were computer based using the modes of researching and problem solving. The components were being tested as part of a proposed commercial publication to be called ‘Astronomy Village 2’ (voyager.cet.edu). Many of the activities observed involved the student finding and reading text on-screen then answering comprehension exercises on paper worksheets.

Figure 11: Science laboratory with circus of experiments, some of which are computer-based.

In another classroom teacher KF was teaching social science to 31 twelve-fourteen year old students. This was a class on Ancient Egypt. There were several activities for students to do. One was to produce their own ancient papyrus, ageing the paper, and using vivid colours, including gold, to illustrate the hieroglyphics they put onto it. Another activity was to use the eight computers in the classroom to run the Microsoft simulation program ‘Age of Empires’ and get the information needed to fill in a worksheet which required students to summarise information about the general period, and the specific functions of certain members of the social structure. When asked to illustrate the reaction of students to the integration of ICT into their learning, KF said that they tried to stay behind after class to continue their process of building an empire on the computer. This was not usual in her other classes!

6.2.1.4 Professional development

The school did not appear to have a consistent approach to ICT professional development. The district calendar showed one day per year for systemic PD, and one day per year for school-based PD. However, the researcher was told by SS that most staff based their professional development around the requirements for teacher registration renewal. Most ICT training was sourced and undertaken at a personal individual level.

6.2.1.5 Stage of development

ICT was integrated into classroom practice in ways which made existing subject study more interesting or more motivating. However, there was little evidence that the content had changed and learning continued to be based upon large group instruction in subject classroom spaces.

6.2.1.6 Issues arising

· To what extent does school administration model the integration of ICT into its practice, and how does this affect student attitudes to integrating ICT into learning (especially when other schools have computerised their option course selection and Roosevelt Middle has not)?

· There was considerable lag between the publication of national ICT standards for teachers and students (International Society for Technology in Education, 1996 & 1998) and their adoption by the educational district for Roosevelt school (Russell, 2000).

· Particular teachers (such as DM2 & KF) have been able to make a considerable impact upon the learning of their students by using ICT to make linkages with external facilities (e.g. astronomical telescopes) and blending computer-based and practical activities in the same lesson.

· The use of web-based activities (e.g. by NN) was increasingly making it possible for students to undertake them outside the school premises. This prepared them to use this learning mode in further study at Lane Community College.

6.2.2 Case Study 2 - South Eugene High School

Figure 12: South Eugene High School

|

|

|

http://www.sehs.lane.edu/ |

6.2.2.1 Background information

|

Age Range |

14-18 |

|

Students with home computers |

70% |

|

Enrolment |

1839 (as at Nov98) |

|

Student:computer ratio |

19 : 1 |

South Eugene High school is officially described on the County web-site as follows:

South Eugene is recognised by the U.S. Department of Education as a premier high school in the nation. … Computers are incorporated in an interdisciplinary fashion, allowing students to use contemporary technology in their academic explorations. Two computer labs are available to students with Internet access and e-mail service. (http://www.sehs.lane.edu/)

The generation of income through student-run businesses was particularly important to the development of information technology in the school, with a significant number of workstations paid for through Yearbook sales (to members of the school community). On the other hand, it was astonishing to the researcher that nearly half of the student workstations had had TCP/IP protocol stacks disabled to prevent Internet access in locations that were not permanently supervised by staff to ensure compliance with school policies on acceptable usage. The previous information technology teacher, Tom Layton had left South Eugene High, to set up the CyberSchool for the District.

6.2.2.2 Policy formation

Figure 13: Computer laboratory at South Eugene High School.

The computer coordinator (BJ) responded to an initial enquiry by the researcher about policies for the cross-curriculum use of ICT by examining the mechanisms in place to control and monitor student access to the Internet. It was clear that this was a topic of some debate within his context, and this was why the question had been misunderstood.

We have a 4J policy that covers the entire district. To break it down, and keep it simple, what they want to do is to make sure kids are getting free and safe access to the Internet, and they kind of break it down in to ags groups, in terms of; in order to get an e-mail account, if you are in grade school or middle school, you have to have your parent’s permission. And then it has to be teacher permission too. But in High School, it is just parental permission. That’s going to be a sticky issue for me, because kids now can go out on Hotmail, Yahoo, and get their own e-mail account and I have no idea if they have their parent’s permission. ... (BJ2)

A second enquiry indicated that there was no general policy at the school level for integrating ICT across subject disciplines, but this was happening to some degree. This process was very much centred upon BJ’s custodianship of the principal computer laboratory. This custodianship was important because it was a role handed to him by his predecessor, and because of the scarcity of computer workstations.

Well, what happens here is that, if a teacher wants to come in and use the lab, which is the best format for them, because they’ve got a whole bunch of computers in one area, and you can put in 30 or 40 students, they are going to come to me with a design, or an idea for a design, in their program for a one day, a three day, whatever, project. And then I kind of walk them through that in terms of…. (BJ 4)

On the one hand BJ saw his role as that of facilitator and design consultant, yet on the other hand his role was more that of a gatekeeper to the technology. This mediation process was emphasised by the design of the laboratory he kept. The raised dais of the control centre, and the shuttered-like appearance of the framework around it, gave a commanding view of the workstations used by students. See Figure 13. One of BJ’s concerns was the differential between the degrees to which the younger teachers incorporated IT into their lessons, compared to the much lesser degree of inclusion by older staff members.

BJ: And they do. They come to me a lot; it’s a new thing, for teachers here. Before I was hired, there was not a lot of use of the lab unless there was a very computer savvy teacher. We are also facing a transition, nationwide, and especially in Oregon, for people are retiring, and so we are getting a lot of younger teachers. And the younger teachers come to me a lot more, than the older class teachers do. (BJ5)

BJ was able to make a link between the extent of policy influence, and the source of funding or resources. He indicated that local funding had been predominant as much as 10 years ago, but this had moved to an amalgam of State and Federal funding initiatives over that period. In his view, this meant that these higher levels of government now had a much greater influence upon policies and their implementation than previously. There was a very clear alignment between participation in Federal programs, for instance, and the adoption of policies produced at that level of government.

AF: Question 3: What policies are there at school district, county, state and national levels that contribute to the way in which IT is used across the curriculum in the school?

BJ: Right now there isn’t, although I think as more funding is.., because 80% of our school district funding comes from the State-Federal level. That’s a big reversal from 10 years ago. So instead of being based upon your local taxes, you’re getting everything from the state level and the Federal level. I suspect we will see that, but right now we are not getting a lot of impact from them, other than in the media. They don’t have a big list of things we have to do, this way.

AF: Have you seen ISTE’s NETS standards?

BJ: Yes, I have seen those. And part of that is because almost all, a lot of their money came, the grants they got, were Federal. So when you start getting the Federal grants, you got to start playing by the Federal rules. Now, we currently don’t have any big Federal grants going on in this building, ... if we did... we’d have to start dealing with it. (BJ9-12)

The student computer ratio in this school was far higher than the national average, at about 19 students per computer. BJ's view was that only two high schools in the city came even close to the national average for this ratio, and in the case of South Eugene High, one-third of the available machines were not connected to the Internet. He realised that sources of funds for new technology needed to be made to flow more readily into his school, and part of the reality of the situation was that private, and commercial sources, would be as important in the future as government funding.

AF: Not just capital money, but continuous money, to keep up to date.

BJ: The only newer computers are in the labs, where we have made a conscious effort to keep up. The exception is in the publications area, where she raises money through advertising, that’s where half her money came from over the last two years to upgrade her machines. We don’t quite have the same opportunity. I’m looking to see if we can advertise on our web-page, but I don’t think we will be able to raise the same kind of money. (BJ21-22)

The atypical student computer ratio contrasted badly with the other perceptions of the school within the community. Students were perceived as being willing to do extra study, not just whatever it took to pass the class. A very high proportion went on to college each year, so there was a common understanding of the developmental pathways that they were progressing along. The proportion of older and more experienced staff was therefore perhaps higher than in other similar schools. BJ considered that this situation had contributed to the funding crisis:

My other battle is ... these are older teachers, and they have no interest whatsoever in giving up money for computers because they don’t use them in their curriculum. (BJ 20)

BJ believed computers were going to be integrated into many school learning areas, and he was strongly supportive of this. This led him straight on to considering the CyberSchool in the area, which had been promoted by his predecessor and was designed to facilitate home and extra-curricular learning activities. The researcher considered that a critical value for the success of such a venture would be the penetration of home computer access. BJ's reply was interesting in two ways; because of the great extent of good quality home computer access, and the subsequent perceived impact upon the home-school relationship. By contrast the school was a much less computer-rich environment:

AF: Yes. Question 7: What proportion of the students would you estimate have access to a computer outside school?

BJ: About 70%. A lot of the kids in this school have access to computers at home. After the summer break, I have kids come in with $5000 systems - and all I can say is you’re lucky you’ve got a lab in school you can come to!

AF: Question 8: Do your policies cover the relationship between home and school computing?

BJ: That's a new area for us. We are trying to do that. I think our biggest issue is that we don't have a big enough communication with the parents and what their kids do with computers at home. Now that’s something parents should know. I think Johnny or Jane go up to the bedroom and start doing their own thing, and those parents have no idea what it really is unless the kids say, here look what I did! And that’s a big battle, getting parents involved with what’s going on.

AF: How about sending attendance home by e-mail

BJ: Well, actually, we’re starting a new pilot program called Achieve.com. (BJ31-36)

The high proportion of students with access to a computer at home contrasted starkly with the low levels of access in the school environment. To exacerbate this further, the really expensive and powerful systems at home contrasted with the computers available in the school, which were generally five years old, and which no longer functioned very well, if at all, with the newer software. This situation illustrated technology operating as a driver, whereby the school was under pressure to implement change.

6.2.2.3 Implementation and practice

The <Achieve.com> website mentioned by BJ was a commercial activity aiming to facilitate, and thereby profit from, links between home and school. This commercial venture hoped to fill a market niche by providing database management functions and by hosting school records in a protected environment. BJ was quite enthusiastic about this, because he saw it as providing facilities he would otherwise have to invent and maintain at the local school level. He was willing to participate in a trial of the system to gauge the reaction of both the school and parental community.

SB was the Publications teacher at South Eugene High. She ran the journalism classes, and taught classes that produced the Axeman monthly Newspaper, and the Yearbook. The latter sold for about $20. This was an important revenue-raiser for this area of the school, providing good access to new ICT equipment.

Figure 14: Logo of South Eugene High School used for newsletter.

These last two operations are supported by the school by allowing English credit (every student requires a minimum of 3 years English credit to graduate) for the Journalism classes. SB requires the students to have passed her Journalism course to start work on the Newspaper. There were no entry requirements for working on the Yearbook, which attracted elective credit.

When asked about the way in which her courses relate to District policies for computers across the curriculum, SB answered “What policies?!” The only one that might apply, about Internet safety, was not relevant to her class machines, since they were no longer connected to the Internet. She asked for them to have this facility disabled since she could not supervise them all the time, and students were more disturbed by MUDS and MOOs than she felt worthwhile. There were no systemic assurances that students should reach a defined level of computer literacy. When asked if she knew about NETS (ISTE) she said she was ignorant of this.

When asked about the number of students who have computers at home, she said that in the last couple of years it had become easy to teach her Journalism class about PageMaker. This was because nearly half of them had already learnt to operate it at home, and she found they taught the other half of the cohort very quickly. In general, students got their keyboarding skills in Middle School, and there were no specific classes in High School. There were many students however, who still needed the opportunity to obtain or refine these skills. Speech recognition software such as Dragon NaturallySpeaking was not available in the school.

6.2.2.4 Professional development

At the time of the research visit, professional development was considered a personal responsibility for teachers. However, some time later the involvement of the State had resulted in directives to the school site council requiring it to “develop plans to improve the professional growth of school staff” and to “administer grants for staff development” (South Eugene High School Site Council, 2002). The computer coordinator gave a very limited amount of peer training:

[Younger members of staff]… are a lot more comfortable with the technology. I put together a couple of seminars every year, trying to induce older teachers to come in and start experimenting. (BJ6)

6.2.2.5 Stage of development

In this school there were difficulties with integrating ICT into more than a narrow range of subjects. This range was mostly concerned with the study of ICT, or with learning the specific skills to operate ICT (e.g. in the desk-top publishing classes). The difficulties related to the relatively low student:computer ratio as this gave the computer coordinator a significant gatekeeping role to ensure none lay idle for long. The low level of access was exacerbated by the policy requiring every Internet-connected workstation to be visually monitored by a teacher. This had the effect of reducing the number which were fully operational in this sense to half the workstations installed.

Limited equipment and internet access inhibited the integration of ICT into all curriculum areas, and hence the school was not assimilating it fully into teaching. Much of the student use of ICT was concentrated on ICT-specific subjects, which dominated the available computer laboratories.

6.2.2.6 Issues arising

· Staff at the school felt the only significant ICT policy concerned appropriate use of the Internet and the restrictions this made necessary.

· Third party service providers were emerging to facilitate the relationship (through electronic mediation) between the school and its community.

· The CyberSchool was emerging as an alternative non-campus specific authorised alternative to conventional schooling.

· Progress appeared to be limited by a relatively poor student:computer ratio and restricted Internet connectivity.

6.2.3 Case Study 3 - Lyceum Descartes

Figure 15: School logo for Lyceum Descartes

|

Tartu Descartes Lyceum Anne 65, 50703, Tartu-7 ESTONIA |

|

6.2.3.1 Background information

|

Age Range |

6-18 |

|

Students with home computers |

15% (including parent’s work computers) |

|

Enrolment |

1000 |

|

Student:computer ratio |

45 : 1 |

Lyceum Descartes is a school in the southern town of Tartu (see Figure 27). Well established Tartu University is a major employer in the town, which has a population of about 150,000. One guide wryly pointed out that having the University 240 km from the capital suited both politicians and students very well: the government could aspire to liberalism, knowing that student radicalism could not threaten the capital.

Figure 16: TE in front of Lyceum Descartes

The school building dated from the time of Russian influence, and this was reflected in its architecture. Another school stood just 200 metres away, and the two were physically indistinguishable. Each was a featureless blockhouse, some 100m long and 4 stories high, constructed almost throughout of solid concrete. The schools were in featureless grounds, with no sign of play equipment for the younger pupils, although good-natured construction of snowpeople was in evidence in late November. The design is partly determined by the environment. The whole of Estonia is a very flat country, with just one peak reaching a mere 300m. Windswept, except where massive co-planted birch and fir forests give shelter, winter comes early and with intensity. The river freezes over in Tartu by mid-autumn. The interior of the Lyceum is similar to the outside, with a wide internal corridor and classrooms on either side on each floor. Stairs were worn smooth by the traffic, bringing softness to the concrete flagstones.

6.2.3.2 Policy formation

All students use the computers, although only 200 use them regularly. Students in the early years of schooling access a learning environment on the web at www.miksike.ee. Students learning French use them, and Mathematics students use the StudyMaster programs. One teacher of music uses them with her students to study musical history and other topics. Policies governing the use of ICT did not extend to the use of student’s own or home-based computers. National policy development in this area had been impeded by a lack of critical mass of computers in this or any other school (TE35). Therefore no comprehensive policy document defining how computers were to be used across the curriculum was available. It was clear that the use of computers was optional (TE42). It was also not accepted as proven that ICT improved education, and therefore the pedagogic rationale was not assumed (TE19).

6.2.3.3 Implementation and practice

Computer provision was situated on the third floor in this school, marking its proximity to the older students. A demonstration room had been reserved for in-service training, equipped with a video-projector, laptop computer, video recorder and very large television screen. A common room for students aged 17-18 had comfortable chairs and tables, and about 6 computers in the corner, all very intensively used, particularly for e-mail. Although these machines ran Windows, the school e-mail system was normally accessed using PINE, a Unix command line package using a terminal emulator logged into the school server. An off-line capable mail package such as Eudora, or a web-mail system may replace this, but both would require more powerful client workstation technology than available within the school at the time the case study was conducted. Further down the corridor lay the main computer laboratory, with 16 workstations. The layout of this room exhibited good design criteria, with all the workstations around the periphery and provision for a projector for demonstrations at the focal point. It was reported that the room was intensively used, with lessons being so crowded that anyone using a computer had 3 people waiting to use it subsequently. Chairs were highly utilitarian, but the teachers said this was good, because they needed to be strong to take the intensive handling in this room.

Figure 17: Main computer laboratory in Lyceum Descartes, Tartu

A teachers’ computer room and a server room adjoined the laboratory. The teachers’ computer room had the latest equipment, and was used for activities such as lesson preparation.

As a guide to the activities undertaken by the 200 regular users of the computer facility, the following were mentioned:

· Primary students used the interactive learning environment www.miksike.ee

· Mathematics students used StudyWorks, one of the packages distributed on the PHARE 3 CD-ROM.

· Students have participated in several online simulation activities by e-mail such as Simuvere or Gaia. The latter compressed 8 simulated years into one school year, generated two competing news-sheets, involved the study of ecology and a reunion of those students who had participated.

Discussions with the Computing Coordinator and technical support staff revealed the following ICT set-up in the school. The school web site was www.tdll.ee with the Internet server running on the Windows NT operating system. The school fileserver was an AMD 266Mhx/128M/9G/FreeBSD 3.0 machine, with a programmed replacement being a Celeron 400/128M/12G/FreeBSD 3.3. Space allocation on the fileserver was 10 Mbytes per user, and all students from grade 11 had accounts. All students from grade 8 upwards had e-mail accounts which they accessed using terminal emulators to run the Unix PINE program. Since the server was permanently connected to the Internet on a 1 Mbit/s Interrad radio-link, students with home Internet access through an Internet Service provider could read their mail outside school hours. Others had also enrolled in free web-based e-mail accounts such as Yahoo and Hotmail.

6.2.3.4 Professional development

The PHARE-ISE project was providing specific software training to teachers. This was limited to software which was written for English-language users and was provided by consultants from Scotland and Ireland (TE35). It had been found that good practice was fostered by the use of worksheets to guide student use of generic and curriculum software packages (TE38).

6.2.3.5 Stage of development

The work of teachers had changed very little in response to the availability of ICT equipment for students. The optional status of its use and limited access meant that few students used ICT as a regular component of their curriculum. Since computer-focused courses were the principal use of the equipment for learning, this indicates the school was working at an introductory stage. However, there were indications that some elements of other stages were emerging, such as the investigative use of teacher-created ICT tutorials in Mathematics, home access to student e-mail facilities provided by the school and participation in online simulations.

6.2.3.6 Issues arising

· The parameters for ICT use were low on measures such as student:computer ratio and home access to computers. However, using the figure of 15 percent for student access to computers out of school, there were about six times more computers available at home than in school.

· Independent and online learning was a feature of some computer use, with a web-site for interactive student work based on worksheets and a tutorial framework program distributed to schools on CD-ROM.

· Professional development was still at the operational stage, with teachers learning how to operate software packages. No clear pedagogical rationale for integrating ICT into the curriculum had yet been accepted, so this aspect had not been incorporated into the training of teachers.

· The use of a wireless broadband link to the Internet was far in advance of many other schools in other countries.

6.2.4 Case Study 4 - Pärnu Nüdupargi Gùmnaasium

Figure 18: Pärnu Nüdupargi Gùmnaasium logo from school web-site

|

Pärnu Nüdupargi Gùmnaasium Pärnu Niidu park 12 Pärnu, ESTONIA |

|

(http://niidu.parnu.ee/)

6.2.4.1 Background information

|

Age Range |

7-18 |

|

Students with home computers |

20% (half also have Internet) |

|

Enrolment |

430 |

|

Student:computer ratio |

31 : 1 |

Pärnu lies at the head of a sheltered bay on the western coast of Estonia. With silver sands on the beach, it was the summer holiday destination of the Russian royal family. Tourism continues all year round based upon the curative muds of the area. The town had a population of 51,807 in 1997 (Cornell, 1999, p. 3). As one of ten schools in this seaside sanatorium town, Nüdupargi Gùmnaasium was upgraded to full secondary status, taking groups of seventeen and eighteen year old students from September 1999. Its previous record as a Tiger Leap school had been mainly established with primary students.

Figure 19: Pärnu Nüdupargi Gùmnaasium

6.2.4.2 Policy formation

The school’s success has been mainly due to a single teacher (VT) who introduced a general curriculum for the integrated use of computers and who used software in imaginative ways. The general ICT inclusion curriculum was originally devised just for VT’s own students. It covers a single 45-minute lesson each week. However, all the teachers in the school now use it. VT devised the guideline curriculum without reference to other sources of advice. There is no direct physical link between home computers and the school network, but students are allowed to print out worksheets at school and take them home. Students are not allowed to bring disks from home into school because of a fear of virus infection.

Students normally use the computers for a range of activities. The examples below illustrate the use of ICT for publishing, and the graphics program Kidpix is also used. Some twelve year old students have e-mail accounts, as well as all those sixteen years and older. Students use about 1000 worksheets from the MIKSIKE web-site. Computers are used for problem solving, sometimes as part of educational games, such as memory blocks.

6.2.4.3 Implementation and practice

The school computer workstations are all connected through the local network to the Internet using an ISDN line at 64 kbits/sec. The class started with a short introduction to the task presented using the LCD projector. Students stood around VT as she described how they should open a given file on the network fileserver and use it for a language study. The text was to be analysed to fill in the answers to a crossword in the document, and all verbs were to be identified by underlining. The students are expected to complete this task in 15-20 minutes, and then are allowed to play (educational) games for the remainder of the 45 minutes lesson. In practice, only some of the students finished 10 minutes before the end of the lesson.

Figure 20: Filling in a crossword constructed from a table in Microsoft Word.

As an example of the integration of ICT into the curriculum, this certainly showed that students were using the equipment. The focus of the learning was on the development of language skills, rather than computer operations. The students were evidently already familiar with the software, and this skill was used as a scaffold for the higher-order language skills the teacher wanted them to work on. In the terms and conditions set by the teacher, it appeared that students would be given an opportunity for autonomous learning once the set exercise had been finished, but it was unclear as to the extent and nature of this activity.

Another group of ten year old students was observed using the computers for a literacy lesson to support their understanding and comprehension of Estonian language and its grammar. A mixed half of the group (thirteen students) was rostered into the laboratory to complete a computer-based crossword which the teacher had created about local coins (see Figure 21).

Figure 21: Example crossword from Pärnu Nüdupargi Gùmnaasium

Lahenda ristsõna

|

|

1 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

2 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

3 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

4 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

5 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

6 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

7 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

8 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

9 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

10 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

1. Kelle pilt on 5-kroonise peal? 2.Eesti krooni lühend valuutavahetuspunktides? 3. Kelle pilt on 25-kroonise peal? 4. Mis loom on 5-kroonise mündi peal? 5. Kes on olnud Eesti Panga president? 6. Kelle pilt on 100-kroonise peal?

|

Rahahoidmise koht. Kelle pilt on 10-kroonisel? Pank Eestis. 2-kroonise rahatähel olev loodusteadlane. Ülalt-alla: Eestis käibel olev rahaühik on Loe läbi teabetekst ning täida ristsõna. Tabelis liigu nooleklahvidega või TAB klahviga. |

Some teachers give students research activities that require Internet searches. The students are very interested in using computers for learning. Many of them queue up to use them after school. The students might use computer-generated worksheets in Mathematics, Language and English.

6.2.4.4 Professional development

VT was self-taught.

6.2.4.5 Stage of development

It was evident that the demonstrating teacher was incorporating ICT into the curriculum to improve learning in particular areas. This purposeful integration allowed autonomous learning, moving beyond the basic operational skills taught previously. ICT was used in teacher-orchestrated ways, using generic office software in ways which complemented the learning activity. For example, students could type in answers to the crossword which they subsequently found did not fit, and could delete before trying an alternative. It was not possible to verify the use of these processes among the rest of the teaching staff, but it was likely that the school was beginning to integrate ICT into at least one area of the curriculum.

6.2.4.6 Issues arising

· Generic Office software can be used for learning activities rather than for student creative work provided the teacher is prepared to invest the time to create appropriate materials

· A single self-taught change agent can influence by example the entire teaching staff in their use of ICT

· Autonomous learning was an aim even at this early stage of curriculum integration of ICT.

6.2.5 Case Study 5 - Tadcaster Grammar School

6.2.5.1 Background information

|

Age Range |

11-18 |

|

Students with home computers |

75%, one-third with Internet access (estimate) |

|

Enrolment |

1436 (mixed) |

|

Student:computer ratio |

9 : 1

|

Tadcaster Grammar School lies in its own grounds about 2 km outside the town (population 6,121) in North Yorkshire. Sheltered behind a stone wall, and with car parking among mature trees, it gives the initial impression of seclusion and calm. Some of the buildings date back to a time when this might have been a manor house, but others are of more recent construction. When inspected in 1999, it was a growing mixed comprehensive (all-ability) school (Office for Standards in Education, 1999). A very small proportion of students (2.4 percent) was eligible for free school meals. It had a reputation for good teaching, and standards of pupil attainment were well above average (para. 1). ICT teaching was rated as “good” for all pupils (paras. 5 & 29).

There was a freestanding ICT course in Year 7 for all pupils, providing a very good basis for future work within a limited time allocation (para. 33). Subsequently, subject departments took responsibility for further applications of ICT during Years 8 and 9, and there was further specific ICT work in Year 9 as part of the modular arrangements for art and music. The computing coordinator (CI) had been successful in training many of the other teaching staff to use ICT across the curriculum, although the inspectors reported that this was not yet fully incorporated into curriculum planning. Good multi-media pentium-class computers were available to students [62 older BBC workstations were excluded from the student:computer ratio calculation]. Fifty percent were Internet-connected, through a single shared ISDN line at 64 kbits/s (CI47-53). Since the previous inspection in 1995 the school’s use of ICT had changed significantly:

The Year 7 foundation course is well planned and

provides a challenging set of experiences for students. The theme of

“children's stories” provides a stimulating focus. Students are introduced to

graphic imaging, the use of a digital camera, composition using MS publisher

and planning a simple web page in addition to word-processing and other basic

ICT applications. Year 7 students, for example, were experimenting with font

sizes, colour backgrounds, distorted lettering and page design in the

preliminary stages of composing a children’s story. The weakness of the

foundation course is in the limited time available during Key Stage 3 to

develop a comprehensive range of ICT skills. Cross-curricular delivery,

considered to be a weakness at the time of the previous inspection, is now a

strength.

(Office

for Standards in Education, 1999, para. 158)

The core ICT staff had been appointed since the previous inspection and they were well qualified (para. 163).

6.2.5.2 Policy formation

The school’s ICT policies were updated annually by an inter-departmental ICT working party chaired by the computer coordinator in March (CI2) and implemented at the beginning of the following academic year in September. The policies were distributed as four documents (see Appendix 7.3.1):

· ‘ICT code of practice’ governing the acceptable use of equipment & services

· ‘ICT Policy’ defining the aims, objectives, review procedures and management structures.

· ‘ICT Development Plan’ detailing the program of equipment acquisition, deployment and maintenance.

· ‘ICT Cross-Curriculum Programmes of Study’ which defines the embedding of the ICT learning outcomes from the National Curriculum into the other subject areas.

There is a strong link between these locally produced instruments and the policy directives from the national government through the National Curriculum. The locally produced policy in some ways pre-empted the policy changes foreshadowed for the 2000 version of the national curriculum. There was a short course on entry in Year 7 for students to become familiar with the local school information technology environment. This was the foundation for further uses of ICT in the various subject areas in the later years of study which were centrally collated and recorded. In the case of Tadcaster Grammar, national policy in terms of the national curriculum documents had clearly penetrated to the classroom level. The stated rationale for this appeared to be the dual requirements to report individual student progress to the Qualifications and Standards Authority, and regular Inspections of schools, to which Tadcaster had responded in precisely the area of this study.

It was apparent that the school connection to the Internet had been the main focus for attention during the previous policy revision cycle, and that most attention had been upon the guidance and control aspects of this, rather than the potential for cross-curriculum projects.

15. AF: Sure. This is a supervisory aspect - what enablers do you have, to guide use in Geography for instance?

16. CI: Not in the policy, no. That’s done more through individual departmental INSET and that sort of structure. The policy is a one side of A4, succinct, if you like...

17. AF: Thou shalt not..?

18. CI: Yeah. What not to do, what to do, type of thing. In a way laying down the type of provision that’s there so that pupils have Internet access and so on. So it’s really outlining the provision and how to go about maintaining that provision.

19. AF: So it’s up to the subject departments to decide how to utilise that provision?

20. CI: Yes that’s right, in consultation with me. There’s a whole program of INSET and, again, the ICT working party is part of that process whereby departments make known their views on particular issues, or make known their views on INSET needs or whatever. I meet individually with departments as necessary. (CI15-20)

The county authority provides various inputs to schools; ICT policy statements, and guidance to schools on how to produce their own policy statement. Since access to the county advisers has to be paid for, the school has minimised expenditure on this activity by essentially giving the ICT teaching staff a central role in ICT policy formulation (CI11) and responsibility for ICT staff training.

6.2.5.3 Implementation and practice

The relationship with the national curriculum had been resolved by collating ICT activities in all the subject departments onto a master grid showing student progress in the ICT program of study. CI showed, for example, how students covered three of the elements in the ICT program within their English curriculum, doing word-processing and desktop publishing. In Geography students used the spreadsheet program Excel to analyse field-trip data and to model weather patterns. Table 15 summarises the cross-curriculum use of ICT at Tadcaster Grammar School.

Table 15: Cross-curriculum ICT use at Tadcaster Grammar School, from Year 8 onwards.

|

Subject |

ICT use |

|

English |

Word-processing, desktop publishing |

|

Geography |

Spreadsheets for analysing numerical data, charting and weather prediction |

|

History |

CD-ROM searches modelling castle construction |

|

Mathematics |

LOGO in geometry |

|

Music |

Microsoft Musical Instruments Sibelius for writing musical scores |

|

Science |

Datalogging Micro-electronics for All (MFA) introducing control technology using logic boards and simulations. |

|

Textiles |

Desktop publishing |

(CI, 1999)

The layout of the main computer laboratory at Tadcaster was a compromise between space and the needs of teaching. While a projector was installed to give an image of the demonstration screen which was easily visible from the back of the room, the layout did not give opportunity for the teacher to supervise each workstation from a single vantage point. The teaching space was not able to accommodate a range of teaching styles, with only a single seating position available to each student which gave them access to the computers even during demonstrations and other group instruction events.

Figure 22: Tadcaster Grammar computer laboratory plan.

When discussing home computer policies, CI appeared to discover personal contradictory attitudes during the interview. Home computer access was very high, but could not be universally presumed. However, its utility was clearly important and to leave it out of policy or practice would impede development:

64. AF: Question 8: Do your policies cover the relationship between home and school computing?

65. CI: Not [sic]. We have no policies in place at present. One of the main problems has been, and is still, that we don’t rely in any way on home computers. A lot of the students will use their computers to complete homework, and/or communicate with school via e-mail. However, we have not been able to build IT in, in any formal sense, to schemes of work, because we cannot guarantee that somebody has access at home. It does not mean, when we are thinking of policies, that we cannot build it in, because it can be a very useful tool. At the moment we don’t have a policy covering this. What will happen, probably next term, is that there will be, we are going to do a survey of, if you like, of the proportion of home computers and what use parents want the students to make of them, especially in communication with the school. And I suppose in that sort of sense we will build something in based on that. But initially we will be looking at facilitating communication between home and school rather than with other people. (CI65)

The contradictory attitudes appeared to be resolved as CI was speaking. The resolution evolved into a plan of action to gather information and incorporate this into new policy.

6.2.5.4 Professional development

The proposal from the Qualifications and Standards Authority to have a national scheme of ICT training for teachers was public knowledge on the day of the researcher’s visit, but implementation was not due to begin until 10 months later. Therefore in this interim, in-service training (INSET) was the process by which subject departments were able to access computer expertise and then build ICT into their individual curricula.

At this point only about 10 percent of the teaching staff were fully trained (CI27). Teacher professional development in ICT was conducted almost exclusively in-house. There was evidence of success, with the example of Geography teachers getting students to use the spreadsheet program Excel to analyse field data and model weather patterns (CI74-75). However, there was no evidence of transformative applications of ICT, since this training was aimed at covering the requirements of the National Curriculum rather than transforming the subject.

6.2.5.5 Stage of development

There were isolated uses of ICT in most subject areas. Although the entire ICT curriculum was covered by these disparate activities, it was clear that only one or two instances were found in each subject. Therefore, the activity could only be categorised as an early form of integration, since there were many ways in which ICT was not used in each subject. There was no apparent need to do so, since these other modes were ‘covered’ for assessment purposes in other subject areas. For instance, there was no indication that e-mail was used for encouraging writing, or that simulations and modelling were used in English.

6.2.5.6 Issues arising

· A large proportion of computer workstations were antiquated, and while excluded from the student:computer ratio, would require students to learn multiple systems and cause technical support complications.

· Close linkage between national curriculum and practice obtained by diffusion with centralised accumulated reporting.

· ‘Locking out’ of some computer uses from certain subjects because of allocation to other areas.

· Emphasis on appropriate behaviours (regulation) in respect of Internet use rather than contributions to the world wide web (transformation).

· Little evidence of transformation except in policies for intranet development.

6.2.6 Case Study 6 – Applecross Senior High

Figure 23: Applecross Senior High School: entrance and logo

|

|

|

6.2.6.1 Background information

|

Age Range |

13-17 |

|

Students with home computers |

90% (all Internet connected) |

|

Enrolment |

1342 (698F, 644M) |

|

Student:computer ratio |

4.2 : 1 |

A majority (52 percent) of the students at Applecross have non-English speaking backgrounds and it therefore runs a substantial ‘English as a second language’ program (Applecross Senior High, 2002). The school is also a state centre of excellence for tennis, art, music and education of the gifted child. 70 percent of the students go on to University and the school is generally ranked in the top ten government schools by state-wide tertiary entrance results (p. 9). Learning with technology is one of three school priority areas (p. 5). There is a favourable staff:student ratio of 1:14.5 (Education Department of Western Australia, 2002, p. 4) which is stable, with 45 percent having been at the school from 5-15 years (p. 7). The Computer-Aided-Design laboratory is one of the best in the state, running commercial and industrial level packages (p.12).

6.2.6.2 Policy formation

The school ICT policy, first drafted in 1998, has been progressively maintained by an IT committee which has a voting member elected from each learning area (KM6). In 2000 a systemic ICT initiative provided an opportunity to access significant funds providing the school focused on state-wide curriculum framework overarching learning aims which emphasised the skills students need to locate, obtain, evaluate, use and share information; and to select, use and adapt technologies (KM20; Education Dept. of Western Australia, nd, p. 3; McCarthy, 2000). The school’s two IT coordinators have 80 percent teaching loads, funded from this government allocation for ICT, which most other schools put into equipment acquisition. The strategies adopted to support these new policy aims included professional development for teachers to become competent to integrate learning technologies into the curriculum, equipment acquisition and network support staffing. The last strategy resulted in the appointment of a recently retired science teacher on a part-time basis to provide technical support (KM6).

All schools in Western Australia were given a free choice of platform, and this has resulted in the school using a mixed platform strategy with about 15 percent of the student-accessible workstation fleet being Macintoshes (KM24). Most workstations are leased rather than purchased outright, and formal laboratories have both colour inkjet and monochome laser printers. The Internet connection had recently been upgraded to give broadband high speed access through a satellite dish, and the initial distribution of this resource was to be 150 Mbytes per student per month. The estimated cost was AU$1,000 per month. All workstations are connected to the school network. The bulk are concentrated in four laboratories, with others in mini-labs associated with the library, and smaller groups of at least six machines in particular subject area classrooms such as English and Art. Staff are supported by about 55 computers, connected to the network using a V-LAN (virtual local area network) to maintain security. Many of the staff have participated in a scheme to purchase individual laptop computers, although some are waiting for this initiative to include the Macintosh platform. The school has started to install equipment to support wireless networking of these laptops.

6.2.6.3 Implementation and practice

A particular issue in Applecross has been the central electronic storage of teaching material. The initial approach was to have a read-only shared drive and staff put digitised materials everywhere on this. It was re-organised in 2001 into learning areas, and then the year groups. In addition, the library installed an information management system called AIMS used to search for material by author, title etc. More recently a digital library system called Masterfile was implemented, which also had an assets management module. This will require a new server, but offers the advantage of being user-aware, so grade 8 students will be shown information relevant to their age-group. Ultimately this information portal will replace the shared drive, and will be accessible from students’ homes:

50 KM: What we are endeavouring to do, and this is down the track, is giving the kids access to our library resources and their folders from home. It will happen [in the future] using Virtual Private Networking, so long as it is safely[sic]. We will implement our new library server, and that is what we will use to implement it. Our intranet page has our daily notices as a PDF file, and we put our newsletter on it as well. (KM50)

There is no agreed level of IT skills expected of students from feeder primary schools. The adjoining primary school has recently been given a funding package to explore the viability of a thin-client capable of supporting external access. This provides a very large central server with multi-user software, allowing relatively old or low-powered workstations to connect to the server and run highly advanced software. Therefore, Applecross Senior High is currently in a transition phase where a strategy for dealing with dramatically different skill levels of new students will be devised.

The interchange of data only between homes and the school is permitted via floppy disk or e-mail. One consequence has been a cost to the school to upgrade the standard school word-processing application to make it compatible with files brought from home. Tension about home use of computers was noticeable in the interview with the ICT coordinator, KM:

57. AF: Can we go back to home-school computing. Do students ever get homework set where they are expected to use a computer?

58. KM: I guess they actually do. I teach Information Systems and Digital Media. I do expect them to do some development at home. I don’t specifically say, but the inference is there that you should be able to do this at home. But you obviously can’t say that because you can’t expect the students to have a machine at home.

59. AF: You can have that debate with teachers, when they have to see they are disadvantaging the majority if you don’t exploit machines at home. Do you have to wait until you have 99% home ownership before you acknowledge them?

60. KM: [laughs] Yes! You can go into a class and ask what the current percentage is now. It’s a tricky one.

I teach all upper school subjects. And I am very surprised when I get a handwritten assignment. I actually have only one student who gives me handwritten work – everything else is word processed. Even though it is not stated, virtually everything is done on computer.

For the Information Systems course, sufficient material has been assembled in digital form on a shared access fileserver folder for all the classes for this Year 12 subject. This modularised material is used in all lessons by the students as a resource, in conjunction with a textbook which is replete with internet web-links (such as: www.howstuffworks.com).

HB teaches Mathematics in Years 8-12. He has a responsibility for the academic enrichment program for gifted students in Years 8-10, and he supports this with a small number of computers he has managed to get the school to allocate. They reside along the back wall of his classroom (see Figure 24).

Figure 24: Academic enrichment mathematics classroom, Applecross Senior High.

He uses the computers to support gifted students who are given week-long learning targets, some of which they achieve by using computers at home. He also uses them as part of general Mathematics courses through interactive web-page reference lists (see Table 16) which are accessed by one third of the class in rotation to break hour-long periods into smaller parts, to improve student motivation and to focus on particular topics. He claimed that twenty percent of his teaching is supported using this technique.

Table 16: Year 11 Mathematics interactive web-site references.

|

Topic |

Web-site References |

|

Linear Functions |

http://www.exploremath.com/activities/Activity_page.cfm?ActivityID=18 |

|

Cubics and other functions |

http://www.univie.ac.at/future.media/moe/galerie/fun2/fun2.html#sincostan |

|

Matrices |

http://www.sosmath.com/matrix/system0/system0.html |

|

Probability |

http://www.staff.vu.edu.au/mcaonline/units/probability/prorul.html |

Students bring their own graphical calculators to these classes, and connect them to the computers. Information can then be transferred from the calculator to storage on the school fileserver, or from a web-site into the calculator. HB directs students to sites such as http://www.casio.co.jp/edu_e/resources/ to download appropriate interactive software that runs on their calculators. HB has found that students are very positive about this use of computers to support the curriculum, and that many undertake learning activities using internet connections at home. His motivation for using these techniques stems from personal altruism and the appreciation of student motivation that it engenders. Also, HB appreciates the increased ease of classroom management. He is of the opinion that this strategy has protected the school’s standing in external mathematics assessments against increased competition from new independent schools in the area.

WL takes a Year 10 academic extension class in studies of society and the environment with 5 boys and 29 girls. He integrates computer applications into this class by requiring them to word-process assignments, prepare PowerPoint presentations of different landforms (using images gathered through home internet connection and from a library of useful images that were placed on the school’s shared server folder), e-mail climate maps as attachments and construct web-sites: see <www.nhc-entries.com/nhc13/nhc13 & www.nhc-entries.com/nhc33/nhc33>. The students told the visiting researcher that they are generally positive about this mode of learning because:

· It is easier to get information from digital resources than from books (no scanning or other manipulation required to include it in your work)

· Information in digital form is generally more up to date than printed material.

· It is easier to locate and find information in digital format.

Other students demonstrated a web-site they had constructed to show their understanding of the formation and exploitation of petroleum oil (at www.icantbelieveitspetroleum.cjb.net) which required a great deal of work. They estimated they spent 25 hours devising the site, 70 percent of which was done on their home computers.

6.2.6.4 Professional development

Teacher professional development was largely undertaken in-house using local staff expertise. An annual survey derived from a state-wide instrument was used to gather data about the general levels of staff ICT expertise within subject area groupings. This information was used to set up both a general and a targeted professional development seminar series, and to provide point of demand training to individual teachers. The seminar series covered topics which included:

· Classroom computer survival skills

· Introduction to the Internet

· Digital camera and scanner usage

· The more targeted and specialised seminars included:

· Photoshop 5 for Art & Library staff

· Web-page design.

Two recent issues were challenging the effectiveness of this scheme. Firstly, new dumb-client advanced technology was being installed in the adjacent feeder primary school, and the flow-on effect for transition students was a factor for which the high school was unprepared. Secondly, a scheme providing laptops for participating teachers had the potential to expand classroom applications beyond the standard office suite. This diversification could require training beyond that which the current ICT coordinators could reasonably provide. Therefore it was perceived that state government policy was running beyond the capacity of the school’s internal policy.

6.2.6.5 Stage of development

It was evident in the case study that integration of classroom-based office-like applications was the pre-dominant methodology. However, there were some glimpses of transformation in the academic extension mathematics and studies of society and the environment arrangements. The regular use of externally created web-based interactive mathematics activities had the potential to make the learning process more flexible, and hence less dependent upon specific times and places. However, the particular implementation could not be seen as different to providing a textbook with solutions in the back. The teacher appeared to reap greater rewards in terms of easier classroom management because of the interactive nature of these online resources. This made the materials more attractive than print-based resources, giving individual and instant feedback to students.

Extension activity in the Studies of Society and the Environment area showed a limited transformation for a few students who worked cooperatively using home-based computers to create an interactive web-site. They indicated that the bulk of the creative task was done this way, with school premises being used for face to face coordination meetings. Although this was a fringe element of the school curriculum, it does illustrate the potential of this way of working at Year 10 and beyond. The school is evidently moving to a situation where its repository (when the underlying architecture has been finalised) of learning materials will be accessible 24 hours a day, 7 days a week from students’ homes (KM50).

6.2.6.6 Issues arising

When the school’s digital learning materials are available full-time off-campus, the institution may have to confront a series of questions such as:

· Since our materials are now available from anywhere on earth, can students be facilitated in their learning when they take extended holidays?

· How do we decide whether to create our own learning materials; purchase them from commercial sources or use freely available digital materials?

· Do we continue to restrict our student intake to local residents?

· If team-based learning projects which draw upon home computers are going to be used more widely, where do we stand with respect to supervision?

· What will be the final, persistent and reliable system for the central storage of curriculum materials?

6.2.7 Case Study 7: Winthrop Primary School

Figure 25: Winthrop Primary School

6.2.7.1 Background information

|

Age Range |

5-12 |

|

Students with home computers |

85% |

|

Enrolment |

693 |

|

Student:computer ratio |

6.8:1 |

Established in 1991, Winthrop Primary School draws students from families in the middle socio-economic group, many on limited tenure appointments or from Asia. Five percent of the students have regular contact with the English as a second language teacher and Mandarin classes for fifty students are held before school (Education Department Western Australia, 2002b). Ten of the eighteen classrooms were in air-conditioned temporary accommodation on the day of the site visit. There was a very low staff turnover, with many of the original teachers continuing to serve in the school (Education Department Western Australia, 2002).

6.2.7.2 Policy formation

Information Technology across the curriculum was a school priority from 1997 to 2000, and this was supported by additional funding through the technology focus school program. The 2002 Learning Technologies Plan for the school (see Appendix 7.3.2) was produced from the annual revision process first started in 1998 when the Department of Education for Western Australia allocated $80M to this area (SP2). The staff planning committee had been largely led by the advice of the two ICT coordinators, who had contributed to system-wide professional development on using the Internet in Education (SP16). The committee had also accepted advice from additional sources including commercial consultants. ICT-related learning outcomes were defined for each age group, but these were advisory rather than proscribed.

The future direction of ICT in the school was being determined by a systemic policy to limit equipment purchases to approved models, and a trial of Application Service Providers (ASP) to implement an ‘Education to Community (e2c)’ model (Kay, 2001).

6.2.7.3 Implementation and practice

In the classes observed, eleven year old students had used PowerPoint in social studies incorporating animations and word processing to create their own evaluation and cover sheets. A progressive science experiment had been photographed and these images were placed into a word processed record. A popular activity was participation in the Quizzard, a regular set of twenty questions about Australia for teams of students to answer in a competition (http://www.palmdps.act.edu.au/resource_centre/wizard_oz/quizzard_intro.htm), which students also accessed from home. There were two computer workstations at the front of every class since this was where the teacher’s desk and the network connection points were placed. Additionally each group of four classes had access to a ‘mini-hub’ of a further six workstations. Teachers were “happy to share their technology” (SP40), so students from any class could use the computers in others reasonably easily. Wireless networking was used to link six demountable classrooms and the neighbouring pre-primary schools into the school network (SP46 & 50). This allowed students to work with the six laptops outside under the trees, but it got slower with distance (SP34 & 50). There was a perceived difference between the way students used computers at home and at school. “We play games. We Hotmail our friends” (SP58).

6.2.7.4 Professional development

A large proportion of the funding for ICT in the school was allocated to professional development since it was “critical to everything we do” (SP12). Much of this training was provided within the school on a “just in time” basis (SP28), since “there is some PD around, not a lot” (SP26).

Professional development in the ICT was limited through the reticence of the coordinator and because of competing programs. The ICT coordinator felt that “I can’t push my teachers any more” and that she had “no right” to tell them what PD to do (SP26). It was “a long process to get teachers to use IT effectively in the curriculum” and “there are some teachers who will not, will not, move into the 21st century” (SP60). The competing demands of the systemic Curriculum Improvement Program (Department of Education Western Australia, 2000) were considerable, further limiting the time she felt teachers could spare for ICT professional development.

Twelve of the fifty-five staff had taken up PC laptops under the Department of Education’s scheme, the small number explained by the incompatibility of these notebooks with the Macintosh platform standard throughout the teaching areas of the school.

6.2.7.5 Stage of development

There was limited evidence of the integration of ICT into student learning activities. While some new technologies such as wireless networking and video-editing (SP60) were in use, the examples observed (creating cover pages and evaluation sheets) were minor additions to the curriculum rather than integral to it. Links with student homes mediated by ICT were not encouraged because of the perceived difference in the way computers were used in the two places. Students were not allowed to develop PowerPoint presentations at home since they could not print out there.

6.2.7.6 Issues arising

· There was tension between the multi-platform policy of the Learning Technologies plans prior to 2000 and the single platform supported under the notebooks for teacher program. This tension was exacerbated at this school through their adoption of the alternative platform for all teaching purposes.

· Some use of wireless networking and laptops.

· Some teachers were “ostriches with their heads in the sand” with respect to ICT, and this was a considerable challenge for the ICT coordinator: “I don’t water rocks” (SP62).